This morning I wrote something and then fed to Claude (the AI) who transformed it. Here’s what Claude wrote:

THE INVISIBLE LADDER

Sarah’s flashlight beam swept across the cardboard walls for the fifteenth time. Nothing. Just brown corrugation and that weird smell cardboard gets when it’s been in the garage too long.

“This is stupid,” she whispered to her little brother Marcus, who was making his flashlight do loops on the ceiling. “Dad’s pranking us.”

“Maybe the magic wore off,” Marcus said, completely serious. He was four and still believed in everything.

“There’s no such thing as magic ink.” Sarah was eight and knew better. “Dad just wants us off the video games.”

They crawled out of the box and went back to Fortnite, controllers in hand, volume turned so low the gunfire was just whispers. Dad was weird about screens but he’d been in a mood lately, ever since Mom… well, since the funeral. Maybe the cardboard box thing was his way of trying.

Ten minutes later the living room went dark.

“BEHOLD!” Dad’s voice boomed from somewhere. Then he crawled into the box from the other end holding something that glowed purple. “Come back, young scientists! The experiment continues!”

Marcus scrambled back in, delighted. Sarah rolled her eyes but followed.

Inside, the walls were blazing. White letters floated everywhere: ELECTROMAGNETIC SPECTRUM. INVISIBLE WORLD. EVERYTHING YOU CAN’T SEE. The words seemed to pulse.

“Whoa,” Marcus breathed, touching a glowing letter.

Dad’s face looked ghostly in the UV light, eyes too bright, smile too wide. “The electromagnetic spectrum spans roughly sixty to seventy orders of magnitude in frequency, while visible light covers less than—”

“Dad,” Sarah groaned.

He stopped. Blinked. “Right. Okay.” He took a breath and his voice changed, got softer. “Imagine the tallest ladder ever built. Not just to the moon—twice as high as the moon. Yellow rungs going up forever into space where you can’t breathe, where it’s just black and cold and nothing.”

Marcus’s eyes went round.

“Now imagine a fruit fly—you know those annoying little things that buzz around bananas? One of those lands on the very first rung. The bottom one. And it looks around thinking, Boy, I’m really something, standing on this ladder. But here’s the thing—the fly can’t even see the second rung. Can’t comprehend how high this thing goes. To the fly, that bottom rung is the whole universe.”

Sarah found herself leaning in.

“That fly is us.” Dad pulled out his magic marker and drew a ladder up the wall, over their heads, across the ceiling. His hand moved fast, the lines glowing under the black light. “This is everything. All matter, all energy, all forces, all particles, all waves. Everything that exists in the entire universe.” He clicked off the UV light. The ladder vanished. He pulled out a regular Sharpie and made a single tiny dot near the floor. Click—normal flashlight. “See that dot?”

They nodded.

“That’s all we can see. That microscopic speck. The rest?” He waved his hand at the now-invisible ladder. “Might as well not exist. Radio waves carrying every song ever broadcast—invisible. Microwaves cooking your pizza—invisible. X-rays that let doctors see inside your body—invisible. Gamma rays from exploding stars—invisible. It’s all there, all around us right now, but our eyes are basically blind. We’re the fruit fly on the bottom rung.”

The box felt smaller suddenly. Darker.

“Can you see angels with that light?” Sarah heard herself ask. Her voice came out small. “Because Mom said… before she… she told me that—”

“No.” Dad’s voice went flat. Hard. “There are no angels, Sarah. No souls, no spirits, no heaven where Mom is watching us. I know that’s what they told you at the funeral but it’s not real. None of it’s real. There’s no tooth fairy, no Santa, no God, no magic. Just matter and energy. That’s it. That’s all there is.”

The black light clicked off. The regular flashlight clicked off. They sat in complete darkness.

“Mom said she’d always be with us,” Marcus whispered.

“Mom said a lot of things,” Dad said. “She was… she needed comfort. She was scared. People say things when they’re dying that make them feel better. It doesn’t make them true.”

Sarah felt something go crack inside her chest. Like a door slamming shut.

Twenty-three years later

Dr. Sarah Chen (she’d taken her husband’s name) stood in the observation room of the Atacama Large Millimeter Array in Chile, staring at data that didn’t make sense. The galaxy cluster was rotating wrong. Too fast. Like something invisible was holding it together.

“Dark matter,” her colleague said, coming up beside her with coffee. “Has to be.”

“Maybe,” Sarah said. But she was thinking about static electricity. About plasma. About how the entire field of cosmology was built on assumptions that might be completely wrong. How they were all fruit flies on the bottom rung, calling that tiny dot “everything.”

Her phone buzzed. Marcus. Third time this week.

She let it go to voicemail.

Ever since the… incident… in high school, ever since he’d swallowed those pills and technically died for four minutes before the EMTs brought him back, Marcus had been different. Intense. He’d found religion, which was embarrassing. Talked about consciousness and fine-tuning and how the universal constants were too perfect to be random. Like he’d joined some cult, except the cult was just him and a bunch of books about physics and philosophy.

The voicemail transcription appeared: “Sarah, I had another one. I need to tell you. It’s about Dad. Please call me back.”

She deleted it.

The dreams were the worst part. Ever since his near-death experience, Marcus claimed he had prophetic dreams. And the thing was—the terrible, impossible thing—they kept coming true.

He’d told her, six months after he got out of the hospital: “You’re going to meet someone. An Asian guy, works in physics too. You’ll think he’s annoying at first but then… I don’t know, something clicks. You’ll marry him within a year. And you’ll have a daughter. She’ll have Mom’s eyes.”

Sarah had laughed it off. She was seventeen, focused on getting into MIT. Boys were irrelevant.

Then she’d met Kevin at Caltech. Found him insufferable for months (he never shut up about string theory). Then one night working late in the lab, sleep-deprived and punchy, they’d started laughing about something stupid and hadn’t stopped. Married at twenty-one. Lily was born when Sarah was twenty-three.

Lily had Mom’s eyes.

Statistical coincidence. Had to be. Marcus had made hundreds of predictions; Sarah just remembered the ones that hit. Selection bias. Confirmation bias. Pattern-seeking in randomness.

Except he’d only made seven predictions total, and five had come true. The sixth was about Dad, apparently. And Marcus wouldn’t tell her the seventh.

Her phone rang again. Marcus, of course.

This time she answered. “I’m working.”

“Sarah.” His voice cracked. “Please. I saw Dad. In the dream. He was in his classroom and there was this smell like… like sulfur or something burning, and he couldn’t breathe, and—”

“Marcus, stop. You’re spiraling again. Did you take your meds?”

“I’m not spiraling! I’m trying to tell you Dad’s going to have a heart attack! In his classroom! Tomorrow, during third period!”

Sarah closed her eyes. “You can’t keep doing this. You can’t keep predicting disasters that don’t happen and then—”

“They DO happen! The car crash with Aunt Linda—”

“You said June. It happened in July.”

“I was one month off!”

“That’s called being wrong, Marcus.”

Silence. Then, quietly: “Why won’t you just admit that something happened to me? That I saw something real?”

“Because it wasn’t real. You were oxygen-deprived. Your brain was dying. It created a hallucination—a very common hallucination—to help you cope with the trauma. There’s been extensive research on NDEs and they can all be explained by—”

“By what? By random chemical reactions? By meat-computer glitches?” His voice rose. “You know what Dad did to us? He taught us that wonder was weakness. That curiosity about anything beyond his precious electromagnetic spectrum was stupidity. He killed something in you that day in the cardboard box, Sarah. He killed it in both of us. But at least I got to see what’s on the other side before—”

“There is no other side!”

“Then explain how I knew about Kevin! How I knew about Lily! How I know Dad’s heart is going to stop tomorrow at 10:47 AM!”

Sarah’s hand tightened on the phone. The specificity. That was new.

“Marcus,” she said carefully. “Have you been taking your medications?”

He hung up.

The next day, at 10:47 AM Chilean time (2:47 PM in Ohio where Dad taught), Sarah was in a meeting about funding allocations when her phone buzzed with a text from her stepmother:

Your father collapsed at school. Heart attack. He’s in surgery. It doesn’t look good.

Sarah stared at the message. At the timestamp.

At 10:47.

She left the meeting without excusing herself, walked straight to the bathroom, locked herself in a stall, and vomited.

Dad survived. Triple bypass, two weeks in the hospital, mandatory retirement. Sarah flew home. Sat by his bed. Didn’t tell him about Marcus’s call.

On the third day, when he was awake and lucid and complaining about the hospital food, she asked: “Do you remember the cardboard box? The UV light? The electromagnetic spectrum?”

He frowned, thinking. “Oh. Yeah. That was right after your mother… I was trying to teach you something important.”

“What was important about it?”

“That reality is knowable. Measurable. That we don’t have to be afraid of death because there’s nothing to be afraid of. Energy can’t be created or destroyed, it just changes form. Your mother’s energy didn’t go anywhere supernatural—it returned to the cosmos. To the stars. That’s more beautiful than any myth about angels.”

“Is it though?” Sarah heard herself say.

Dad’s eyebrows went up. “What?”

“Is it more beautiful? Because it seems… emptier. Lonelier.”

“Sarah.” He reached for her hand. His grip was weak now, papery. “You’re a scientist. One of the best. Don’t tell me you’re having some kind of midlife crisis about—”

“Marcus predicted your heart attack. Down to the minute.”

The room went very quiet.

“He’s been on medication for years,” Dad finally said. “Schizophrenia runs in your mother’s family, you know that.”

“He doesn’t have schizophrenia.”

“Then what?”

Sarah looked at her father—this man who’d taught her to think critically, to demand evidence, to never accept easy answers. This man who’d drawn an invisible ladder in a cardboard box and told her that everything beyond the visible was just different frequencies of the same meaningless energy.

“I don’t know,” she said. “But I think… I think the fruit fly might be missing something.”

Six months later

Sarah was back in Chile, back at the telescope, back tracking her rogue galaxy cluster, when Marcus called with the seventh prediction.

“Don’t tell me,” she said immediately. “I don’t want to know.”

“It’s about you.”

“Marcus—”

“You’re going to meet someone. An older woman, at a conference. She’ll have a theory that sounds crazy but you’ll realize she’s right. About consciousness. About what happens when we die. About Mom.”

Sarah’s throat tightened. “There are thousands of conferences. Thousands of older women with theories.”

“This one will be in Vienna. March 14th. She’ll be wearing a blue scarf and she’ll drop her coffee when she sees your name tag. And Sarah? When she tells you what she’s discovered, you’ll finally understand why I can see things I shouldn’t be able to see.”

“I don’t believe in prophecy.”

“I know. That’s what makes this so hard.”

Sarah closed her eyes. The dark matter data glowed on her screen—evidence of something invisible, something that shouldn’t exist according to everything she’d been taught, but undeniably real.

“What if Dad was wrong?” Marcus asked quietly. “Not about the electromagnetic spectrum. That’s all true. But what if the ladder goes both directions? What if there’s something smaller than quantum fields, something that exists in a different dimension entirely, something that consciousness can touch? What if Mom was right about angels?”

“Angels aren’t real, Marcus.”

“Then what do you call a dead woman who shows up in her son’s vision and tells him to go back? Who gives him information he couldn’t possibly know? What do you call whatever it is that lets me see across time?”

Sarah opened her mouth. Closed it.

“I’m tired,” Marcus said. “I’m so tired of seeing things and not being believed. But I needed to tell you about Vienna. Because after Vienna, everything changes. For both of us.”

He hung up before she could respond.

Sarah sat in the dark observation room, surrounded by millions of dollars of equipment designed to detect the invisible, to measure the unmeasurable, to prove the unprovable.

Then she opened her laptop and bought a plane ticket to Vienna.

March 14th.

She told herself it was just to prove Marcus wrong.

But late that night, alone in her room at the telescope facility, she pulled up photos from her wedding. There was one from the reception—Kevin laughing, her in her white dress, and in the background, almost invisible, a trick of the light or a smudge on the lens: a bright spot that looked almost like a woman’s face.

It looked like Mom.

Sarah zoomed in until the pixels broke apart.

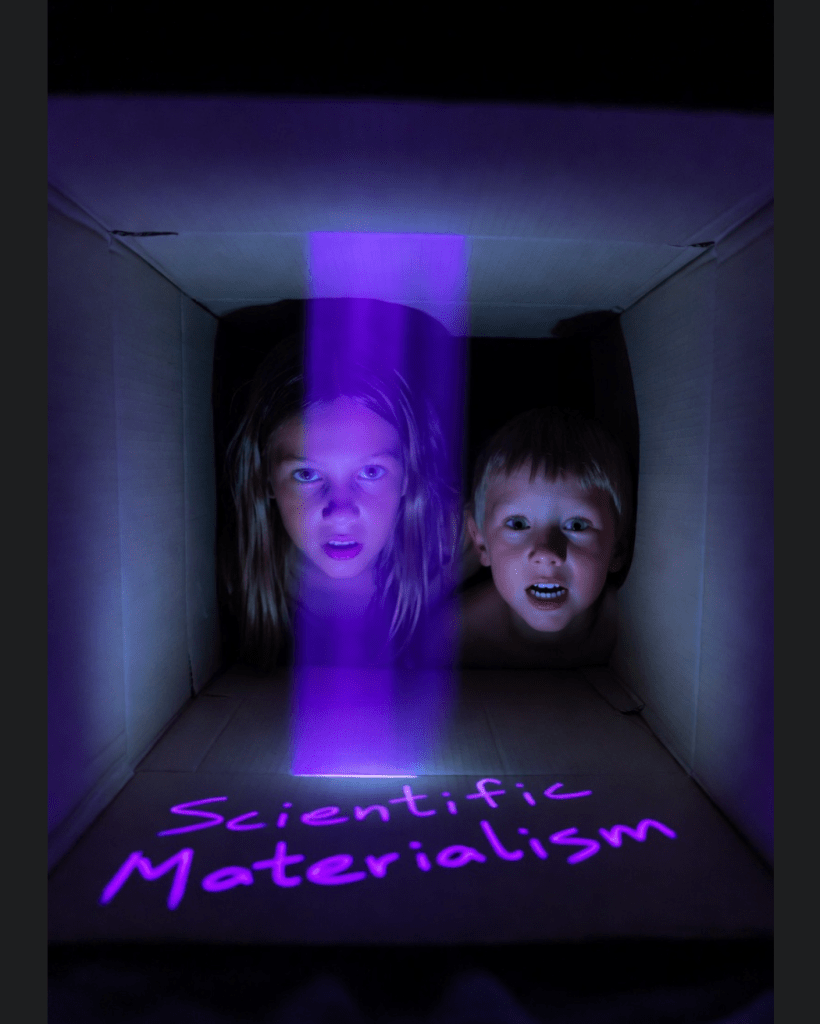

“Scientific materialism,” she whispered to the empty room. To the invisible ladder stretching infinitely above and below. To the fruit fly that couldn’t see past its own rung.

She thought of the cardboard box. The UV light. Her eight-year-old self asking about angels.

She thought of Dad’s flat, certain voice: There’s no such thing.

And she thought: What if you were wrong?

Outside, the Chilean stars blazed—each one a sun, each sun surrounded by invisible forces, dark matter, dark energy, mysteries upon mysteries, rungs upon rungs of an ladder so vast that humanity had barely glimpsed the first step.

Sarah looked up at them and wondered, for the first time in twenty-three years, if maybe—just maybe—the invisible ink was trying to tell her something.

The message was still there.

She just needed the right light to read it.

The End

…………………………………………

In case anyone’s curious, here’s the thing I wrote as the basis for Claude’s short story. I’m putting it here at the end because it’s painfully low in quality compared to what the AI Claude wrote in the twinkling of an eye. (No whine, just fact.) Grok 4.2 drew the picture that I’ll attach near the top if time permits.

Also, fwiw, here’s the prompt I gave to Claude: “……please re-write this without putting any constraints upon yourself. Just try to make it a “page turner” in whatever way meets your fancy, whether humor, a balanced approach, turning it into pure fiction, adding scenes, or whatever else, serious or whimsical that suits you at this time, Claude.”

My writing from this morning that I fed into Claude, AI. Many people would hate my opinion here if they ever read it. Sorry, ya can’t please everybody.

“Scientific” Materialism: The Death of Science and Meaning

(by Morrill Talmage Moorehead, MD)

“Scientific” Materialism is a great evil, possibly the worst influence of all time. It’s a mind virus that imposes boundaries on our scientists’ thinking and blocks their interest in novel, outlier observations and facts that might otherwise bring new levels of understanding to humanity from within the vast realms of the unknown. This dogmatic worldview, wrongly called “Scientific,” is the untestable belief that (randomness acting upon) matter and energy constitute everything that exists or could possibly exist anywhere, ever. While suppressing thousands of anecdotal hints of paradigm-shifting science, this depressing, anti-scientific worldview simultaneously strains to destroy all notions of a higher meaning for human existence or any transcendent purpose for our lives.

It starts with teachers and children who have been legally sentenced to periodic confinement together within the clutches of Western public school systems and their brainwashing effects.

For some kids, it might go something like this…

A brother and sister are playing inside a big cardboard box in the living room, she’s 8 years old, he’s 4. Their dad, a high-school science teacher, wrote a message for them on the inside of the box using “magic” ink. He turned out the lights and gave them each a flashlight, but he didn’t tell them they would need ultraviolet light to read his message.

This would be a teaching moment, he figured.

The kids turned on their flashlights in the dark living room, crawled into the box, and for almost a half hour, looked all over the insides of the box for Dad’s writing on the wall.

Finally they gave up. The eight-year-old said, “Really, there’s no such thing as magic ink. Dad just wants to get us off the video games.”

The two went back to playing video games with the sound turned down so low that Dad hopefully wouldn’t hear the guns and explosive detonations.

Ten minutes later Dad returned with an ultraviolet light on a long extension cord. The children crawled inside the cardboard box from one end and Dad came through the other with the black light that made his message glow:

“Electromagnetic Spectrum.”

The eight-year old crinkled her nose. The four-year-old looked explored the bright white spots on his shirt sleeves.

Dad got that boring sound in his voice. “The electromagnetic spectrum spans roughly 60-70 orders of magnitude in frequency, while visible light covers less than one order of magnitude.”

Both kids couldn’t care less. Grown-up mumbo-jumbo.

“No, no,” Dad said, seeing he’d lost them. “Pay attention now, this is really fascinating. Let’s say you built a bright yellow step latter twice as high as the moon. You could climb up and look down at the moon, right? Picture that in your heads, the tallest yellow ladder ever made. It stands now right out in our back yard. All of a sudden up comes this scrawny little fruit fly with a scowl. It flies up and lands on the first step of your ladder thinking it’s big stuff. But it’s just a pipsqueak and doesn’t have enough brain power to figure it out. Your ladder is like the electromagnetic spectrum.” Dad holds the blacklight up to the glowing letters, “Electromagnetic Spectrum.” This spectrum is ginormous, big, bigger, biggest and then some. It stretches way beyond the Moon. And the fruit fly is like a tiny dot on that spectrum. And here’s the thing, the little dot is the only part of the ladder that people can see. Everything else is invisible.

The daughter’s brow is crossed.

“Think about it,” Dad says. “Everything there is in the whole wide world, in the whole wide Universe, comes from the electromagnetic spectrum and we can’t see any of it except this tiny fruit-fly speck near the bottom. OK, here’s this big ladder.”

He pulls out the magic pen and draws a ladder from the bottom to the top of one side of the box, then on across the flat part above them. “That is literally Everything that exists, and it’s almost all invisible to our eyes. It’s like invisible ink. We can’t see it.”

He turns off the black light and flips on a flashlight. The ladder vanishes. He pulls out a regular pen and puts a dot near where the bottom of the ladder was. “You see that, right?”

Both kids nod, eyes wider now. “That’s the fruit fly. That little dot. It’s the only part of this big spectrum that people can see. And the spectrum is everything that there is. It makes up all matter and energy. And the tiny dot is the only part that we can see without special tools like this UV light.” He turns the black light back on and turns off the flashlight. “Any questions?”

“Can you see angels with that light?” his daughter asks. “Cause Mom said…”

“No, I know what Mom said, but there’s no such thing as Angels, honey. No tooth fairy, either, OK?”

The little girl looks down and nods slowly.

Decades later she’s an astrophysicist who knows that nothing could possibly exist anywhere in the Universe except for matter and energy, the two manifestations of the electromagnetic spectrum. She’s recently heard the term “scientific materialism” but hasn’t thought much about it directly. She does have intuitive doubts about the widely accepted existence of dark matter, the invisible stuff that keeps the arms of galaxies spinning faster than they really should if gravity alone rules the stars. She thinks the popular concept of a dark gravitational force is probably nothing more than an enormous amount of static electricity operating at the cosmic level. Something about like that, anyway. She wonders if maybe we live in an electric Universe, or maybe a plasma Universe, and gravity isn’t actually the dominant force that everyone thinks it is. But whatever the truth turns out to be, it’s going to be governed by randomness. That’s the bottom line.

In a random Universe, nothing happens for a reason, there are no elves, fairies, unicorns, Jinns, Angels, Demons, God, Santa Clause, UFOs, Aliens, or anything else that gullible people believe in. Dark matter and dark energy will probably be added to her list eventually, she privately suspects. In fact, there’s really no right and wrong if you think long and hard about it. Human values are relative to the societal norms of a person’s time and place of birth. We’re not really any different from other animal, we’re just a megaton smarter.

She vaguely senses this vacuum, the literal meaninglessness of the world we believe in and share with a large part of Western culture. As long as she doesn’t dwell on it, it doesn’t bother her as much as it bothers her younger brother. He tried to end his life in High School. It happened right after his first real girlfriend dumped him for a girl. Those were rough times. Her brother nearly died. When he finally opened his eyes in the hospital he spoke of strange things.

“There was this bright light that you could feel… like being in love,” he said. “It felt better than anything. I saw Mom. She said I had to go back, but I didn’t want to.”

To this day he insists that it was real. “More real than us talking right now,” he said to his sister.

And he’s always going on about the fine-tuning of the universal constants and the mathematical odds against random forces ever grinding out the information in DNA.

“He’s wrong, of course,” his sister thought. “Everything is random. But it’s kind of weird the dreams he’s had since he almost died. He told me he dreamed that I would meet an Asian guy, marry him and have a little girl of my own within two years. And by pure coincidence, it turned out just the way he said. We keep this part strictly to ourselves because it’s too strange to tell, even to Dad. Daddy would just launch into some lecture on the commonality of unlikely coincidences. And as always, I wish Mom were still alive. You could tell her anything. And she would listen.”

….

Love and hugs,

Morrill Talmage Moorehead, MD