Chapter 0

Johanna

“The scientists who have developed the case for intelligent design have begun to overcome the prejudice against their ideas and have published their work in peer-reviewed scientific journals, books, conference volumes and anthologies.” — Stephen Meyer, PhD, Signature in the Cell

I’m Johanna Fujiwara, Ph.D.

Years ago, I inspired Talmage to write fiction. He tries to think of me as a character he created. Nothing could be further from the truth.

I look a little like the artist, Promise Tamang Phan, the way she’s painted herself in this video. Actually I’m not as pretty as she, but try telling that to Talmage. My legs are short for my height and my calves are too thick. I call them “daikon ashi” which means “white-radish legs.” Short legs run in my family on my Dad’s side, but they skipped my little brother. Well, he’s big now. Sixteen.

Unless you’re a theoretical physicist, I don’t expect you to believe this, and if you are, you might disagree all the more, but beyond the Universe lie similar Universes, potentially an infinite number, though the heavens aren’t crowded.

As a result, virtually everything that could happen does happen somewhere.

That includes me and every detail of my life.

True, I can’t prove that in a laboratory, but I’m hardly ever wrong. It’s a matter of record.

What’s unusual, I guess, is the fact that I’ve figured out enough to sense what my “coincidental” writer is thinking and feeling. I know when he’s trying to pretend I’m not real. And when he’s honest with himself, he knows I know.

I choose to think of myself as antifragile, a girl with plenty to gain and little to lose. Believe it or not, this quality is the basic human condition. You have it. Antifragility is the difference between biological and supra-biological minds, assuming they exist. There’s decent evidence. I think our ability to gain from many small failures is the reason they’ve come here, assuming they have.

In veiled crafts.

The nature of identity is elusive. Talmage thinks the girl he’s been writing about all these years has always been me because his feelings never change for her.

Could be. But I know this – the seeds of love and meaning are free will and identity. I’m barely nineteen, but I can tell this applies beyond spacetime and the “God of Spinoza.”

Past the sub-infinite hosts of Universes, there’s reality outside of space and time. In third grade I was sent to the principal’s office for talking about it. They said we don’t talk religion in public school.

I couldn’t understand what was religious about it…

Light travels outside of time, but inside of space.

Einstein’s time dilation gives us a number divided by zero when anything moves at the speed of light. If you avoid the myopic logic of mathematicians who apply our internal speed limit to regions beyond…

Dividing by zero yields infinity. Inertial frameworks become irrelevant.

Which means a “wristwatch” on the ground goes infinitely fast compared to a “wristwatch” on a photon.

“Infinitely fast” means that the entire history of the Universe goes by in an instant when you move at the speed of light. Even if you’re a photon of light yourself, or some other fundamental wave-particle.

Hence the irrelevance of time to the diffraction pattern of light crossing slits, one photon at a time. (Here’s a video of that.)

Physicists in your universe think photons and their class have a separate reality. That’s adorable, but wave-particles don’t contain mind, they’re composed of mind. Literally. From a photon’s perspective, all history happens in a moment – in one Planck time.

So when photons, from our perspective, go through slits in single file, things are different to them. They see themselves as all passing through together, bumping shoulders and interfering with each other to give a diffraction pattern that would be supernatural if time were uniform and it were impossible to go outside of it.

My physics teacher told me to shut up when I mentioned this in class. He mumbled it through his teeth, but everyone heard. A red-headed guy behind me said, “Yeah, please!”

School’s no place for critical thinking. They hate it. They love their own dogmas.

From the center of a black hole and the mind of a photon, all history is an infinite holographic snapshot where time means nothing to the diffraction pattern of slit experiments. From there, our unpredictable decisions are known. But it’s not “foreknowledge” because the “fore” of foreknowledge is relative to the observer. One person’s foreknowledge is another’s “after” knowledge, depending on which side of the spacetime horizon you occupy.

That means free will is not an illusion! Please believe me. This point is crucial for your happiness.

Light is “outside of time” or independent of it. But we see light so it’s not “outside of space.”

Dark matter is protomatter that sits virtually outside of space. Its only detectable property from our side is gravity, yet it shapes and positions the galaxies, so it’s “inside of time.” (Here’s a video on that.)

When I was an undergrad, a journal rejected a paper I wrote on dark matter. The editor didn’t mention my paper in his rejection. I was simply not a Ph.D., therefore my paper, my brain, my soul, my existence were unfit for his journal: “Welcome to the cult, Johanna.”

Albert Einstein’s first four papers of 1905 would be similarly unfit for today’s journals. Forget the “miracle year” for space, time, matter and energy. Einstein wouldn’t have had the credentials for these elite morons we’re dealing with today.

The human mind lies partly inside and partly outside of space and time. Miss this, and materialistic determinism will swallow you whole, leaving you convinced that you have no freedom. No choices in anything. You’re a machine with a future set in stone, sweetened by a sprinkle of chance and the “illusion of consciousness” with its “false sense” of free will.

Not a happy place, but it’s the ditch into which our educated subculture has fallen. Call it science, but it’s not. It’s an emotion-based philosophy that, combined with the effects of modern wheat, brings us an ugly stat: 30% of college students are depressed.

The neurons that brought puritanical fundamentalism to the United States have now embraced materialistic determinism and made it the new religion of meaninglessness.

It’s a strange religion that excludes the mind. The fundamental assumption is that matter and energy exist on their own, but nothing else does. All minds are derived from the material world which is mindless, therefore our minds have no reality. The evidence from quantum mechanics has to be ignored to maintain their assumption, but that’s no problem for these zealots. A mindless universe is assumed with the confidence of a Baptist preacher.

I argued this with a brilliant atheist over coffee at Starbucks. It probably wasn’t a date, but he asked to meet me there, so maybe it was – my first date, in fact. When we landed on neo-Darwinism and he saw that I could argue intelligently against it from genetics he hadn’t read, he remembered he’d forgotten something and had to leave.

“We should do this again,” he said.

We never did. He was handsome, if that matters.

The mechanics of the mind lie within space and time (in and around the brain) but free will exists outside of space. By residing outside of space, free will inserts itself as an untouched cause into the web of destiny that fills the material, pool-table Universe.

By residing inside of time, free will remains relevant to history as it unfolds at various changing rates within spacetime.

I haven’t seen where identity lies. Talmage hopes it’s like free will: outside of space but inside of time. That way I’ll always be the same girl, Johanna, no matter what changes.

I think he’s right. I think someday we’ll meet for coffee, because, despite separation, my Universe is remarkably similar to yours. I don’t know why.

I was born in Castle Medical Center on Oahu, Hawaii – one of the few things I can’t remember.

Eleven great years later I killed my brother’s therapy animal, Moody. I wish I could forget the whole thing. I have recurring fight dreams about it. Nightmares, really.

Moody was a chimpanzee. Mom and Daddy were out. I was the sitter. What could possibly go wrong?

James was in his bedroom playing with Moody, pretending to snatch off Moody’s nose and then show it to him. Moody always played along and seemed to tolerated it well, but this time I think James punched the little guy’s face during the nose theft.

I didn’t see that part, but I heard a noise and got up to see what was going on.

Moody’s face was unlike anything I’d seen in real life. It was twisted in rage and looked like a monster. He attacked James, threw him against the wall, denting the plaster. He grabbed James again, threw him to the floor like a rag, jumped on his chest and bit his nose. Pulses of my brother’s blood squirted into the air. Moody spun around and glared at me, then grabbed James’ genitals and tried to pull them off. James screamed like he was dying, and something cold landed inside me. I felt it in my chest as I charged at Moody, shot my right arm around his neck as fast as a cobra, then locked a triangle with my left arm. I pushed my face against the back of his head to protect my eyes from his fingers, held my breath and squeezed with all my strength.

I don’t know how I knew that move. I never watched MMA. I’d never heard of a rear naked choke. I don’t see how it could have been me, honestly.

I was so angry my brain changed perspectives. It sounds crazy, I know, but I swear I was looking down at the three of us from above our heads.

I didn’t loosen my grip for the longest time.

James started yelling at me to stop, but I wouldn’t. Moody went limp, but I kept the choke on him with every bit of force I had. I felt as if I hated Moody and everything about him. But I loved him. We all did.

Finally my muscles couldn’t squeeze for another second. I relaxed my arms but still wouldn’t let go. I was afraid he would spring up and kill us. As I finally started releasing him, he slumped forward and I dropped him face first on the floor. He lay there like one of James’ stuffed animals.

There’s a saying that if you murder someone, you’ll always feel like an outsider looking in on humanity.

It’s true. Even if you murder someone who’s not considered human. Even if it starts out with you trying to save your little brother’s life.

In the emergency room, my scalp needed stitches. Most of my hair was gone. Pulled out, roots and all. I looked like a boy for the longest time. Girls around the island shaved their heads to honor me, Mom said.

One of the ER doctors told my mom that Moody must have been sick. A heart condition, probably, because there was no way a little girl could strangle a healthy adolescent chimpanzee. The doctor said an ape’s muscles are way stronger gram-for-gram than a human’s. The genetic code is identical, but parts of our code are now inverted, as if deliberately taken off-line. Nature does strange things, he said, no curiosity in his voice. None at all. I just don’t get that. I hope I never do.

But really, Moody was healthy. He was stronger by far than anyone else I’ve dealt with.

The truth is, I had an unfair advantage. I’m a descendant of Miyamoto Musashi, the Samurai. The legend.

No one knew. I didn’t. Growing up in Hawaii, I was a “hapa girl.” Hapa means “half” in Hawaiian.

I’m half Japanese, and I thought I was half white – until I got to the University of Hawaii.

At UH I discovered how badly some people are offended if you’re half Jewish and you think that makes you half white.

It happened in front of the biochemistry class. We had to pronounce our names for the professor. I was in the second row. When my turn came, I stood with my back to most of the class.

“I’m Johanna Fujiwara,” I said, and stood tall, proud to be the class prodigy.

He peered at me over the tops of his reading glasses. “You must be hapa,” he said warmly. “Your name’s Japanese, what’s the other half?”

“White,” I said.

He chuckled. “Can you be less specific? Scottish, Irish, Dutch… what?”

“My mother’s Jewish,” I said.

The warmth left him. “Jews aren’t white,” he growled, but caught himself and forced a smile. “You’d almost think some of them were. Makes you wonder. Well, young lady, clearly you’ve got a lot to learn. Have a seat.” The guys behind me laughed.

I felt flushed and humiliated. How was it possible that I didn’t even know my own racial composition? I stuck my tongue out at the professor, just the tiniest bit, but it was enough to notice.

“She stuck her tongue out!” a guy in the first row said, and howled. The whole class laughed at me, professor and all.

I buried my head in my arms wishing I could disappear or hit replay, go back and lie about being half Jewish. In fact, I did hit replay a hundred times that day in my head, but nothing ever changes when you do that.

Three weeks later I ruined the curve on the first test. I always do that in the tougher classes, but this time I felt good about it. Glad to redeem myself and show them how much I really knew.

The professor had the usual tough choice. He could give one A with the next highest grade a C -, flunking the rest of the class, he could make the next test ten times easier, or he could throw my scores out and redo the curve.

On the first test he gave me the only A, and told the class to buckle down. I guess he was proud of his tough reputation. Proud to routinely flunk a bunch of depressed students, thinking that cruelty somehow helped him make his way in the Universe.

After the second test he changed his tune. He said that I was an “outlier.” He isolated my score.

Then he said there was no reason to think of “this ten-year old kid” as a cut-throat.

He damn well knew my name, Johanna Fujiwara. But he wouldn’t say it.

He did say that he didn’t want to hear the term, “cut-throat” applied to “this poor little girl.”

The class cheered. Their grades would be recalculated and catapulted up several notches. They wanted to know if this new fairness would be applied to the first test retrospectively.

“Yeah, I supposed so,” the professor said, giving in.

I’d never been called a cut-throat before that day, but afterwards I heard it a lot. They shortened it to, “the throat,” as in, “The throat’s taking P-chem from Thompson. Better go with Bobst.”

You know, if you find the right phrase, you can dehumanize anyone. Ask Viktor Frankl. He said he found meaning in his suffering at Auschwitz, and everyone can find the meaning of their own lives if they search.

To me, life’s meaning starts by convincing your subconscious mind that it has a free will. For college students, that’s a tall order, but here’s the deal:

You get up off your butt and do something small and deliberate for yourself right now, and work up to doing these simple things all through every day. Instead of looking around the room for your next move, or letting something on your computer screen decide your next activity for you, close your eyes and think: What will I do next? Make the decision, then do it immediately.

Eventually it starts to feel natural to allow your world to fit you, rather than allowing your world to manipulate you and steal your free will. That’s depressing to your subconscious mind who begins to feel imprisoned in your skull.

I graduated number one in my class – just two years after seeing my one and only glimpse of antisemitism. I guess that’s what it was.

But I’m not Japanese or Jewish inside. I’m hapa. To me, “hapa” doesn’t mean “half” anything, it means fully human.

That’s my highest goal, anyway, to be fully human, no longer outside looking in at the real people.

Chapter 1

Competition

My phone is blasting Skullcage from my lab coat near my pillow. I’ve been spending nights in my Prius at the Beach in Astoria since Grandfather died. There wasn’t money enough for the house plus keeping James in Hawaii with his new shrink. This new guy’s actually helping my brother with his depression. It’s the miracle I’ve been searching for.

Talmage wants me to tell you this like a story, so take a look up through the glass of the hatchback at the stars while I find the phone. We don’t want this novel rejected in The First Fifty Pages for lack of a visual scene… or because I’m “breaking the fourth wall.” I bet there’s a rule against that somewhere.

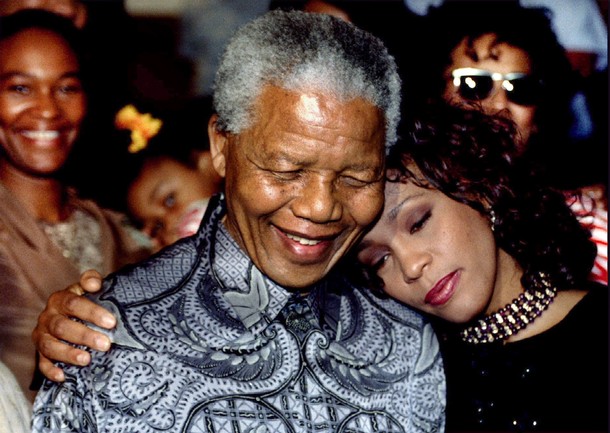

Check out Orion’s belt in my Universe. It looks nothing like the arrangement of the three Egyptian Pyramids, but I have a warm feeling for the man who thought of the idea: Robert Bauval. That’s him in the picture.

I trust his eyes and the way he speaks, because he reminds me of an Arabian geneticist who always has my back at work. She speaks her mind and curses Dr. Drummond for publishing my research as if he were the original thinker and inventor.

Academics eat their young. But the people out there doing my brand of genetics probably know where Drummond’s breakthroughs are coming from. He was totally obscure before my name showed up behind his.

My phone shows 4:11 AM and a Hawaiian number (808) that I don’t recognize. It could be James on a friend’s phone. Now I’m seeing James dead on the side of the road with a cop calling the next of kin.

I have to stop jumping to worse-case-scenarios. It’s part of a rare condition I’m blessed with – perfect autobiographical recall. Depression is part of it, too, but it comes later in life. It probably has no relation to my other condition – M5.

The call is from a boy claiming that he’s kidnapped James.

Oh, brother. I’m just going to hang up.

James has high school friends now, all of them older. My prank caller was probably one of them. They’re different. They say they hate capitalism but actually they hate the overwhelming sense of unfair competition that the adults bury them in at the concentration camps called schools. Life on Earth is tough, but birds and bears get a chance to relax and imagine their own importance while kids have their noses rubbed in the armpits of superior competitors all their waking hours. Giving everyone A’s and trophies convinces them they need handouts to make up for their mediocrity and inferiority. The lies only make the adults feel better, they don’t hide or change the reality of unfair competition.

And don’t tell me it’s fair. I know better. It’s completely unfair because of people like me. I remember everything I see and hear. My brain does complex calculus at the subconscious level. I don’t even know where the answers come from sometimes. And this stuff barely scratches the surface.

James’ new rock band has no name, but he’s always recorded under the banner of Skullcage. He’s the main act everywhere he goes. I’m so freaking proud of him I could pop! He plays all the instruments, sings, and writes incredible songs full of tormented screaming, beautiful melodies and guitars that sound like they’re speaking a language – trying to talk.

His CD’s make you feel confident… unless you worry about him killing himself, which I often do.

You’d never know he’s chronically depressed if you met him. He’s funny, dominant, and full of life. He makes everybody laugh and feel important. You wouldn’t believe all the people who think of him as their best friend. But only one person is…

Me.

There’s a barge coming out of the mouth of the Columbia River to the north. Its lights are all that’s visible. Plus there’s the traction beam of a UFO aimed at the deck. I’m kidding, but what is it? Somebody on a higher deck with a floodlight, maybe.

I’m getting out for a better look.

The waves are slow closeouts tonight, scooting up the long level beach in parallel terraces, white and hissing at the full moon.

But I ask you, what are the freaking odds that the moon would spin at exactly the rate necessary to keep one face aiming at the Earth at all times? We’re talking two balls rotating freely and one orbiting the other. How does that match up without a little help? Someone put all the weight on the side closest to us?

Hello?

There’s more going on here than meets the eye. I wish I could talk to Astronauts like Gorden Cooper https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dvPR8T1o3Dc and Edgar Michell https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7AAJ34_NMcI.

These guys would have a broad perspective and be brave enough to face death and public humiliation.

They’ve seen the entire Earth in one glance – our crucible of survival and our teams – the competitors against the rise-above-it types. But the spectators, where are they?

You don’t set up a game of this magnitude unless you’re planning to sit and watch.

That’s why the moon faces us. It holds the box seats.

The traction beam above the barge went out before I could tell what it was. I’m cold in this breeze so I’m getting back into the car and pulling the hatchback down.

My ringtone blasts again, “Give to me a dirty heart filled with all the darkness of the world. I’m taking all the dull sh*t in and burning up inside within, it’s true. I hate you.”

James wrote this and recorded it on cheap gear when he was eleven. It was a prayer. I could cry… his little face and his little high voice and that huge drum set all around him.

And that melody.

My phone shows the same caller. I answer, and I was wrong. It’s not a high school boy. It’s an old woman.

“I’ve kidnapped James,” she says.

My heart stops and I try to catch my breath.

She tells me to get on a flight from Portland to Oahu at 10:00 this morning. Gives me the flight number and says I’ll meet a guy named Del at the terminal.

I manage to plead. “Let me talk to James so he doesn’t freak out.”

“Well,” she says, “I don’t actually have him yet. I’ve sent a boy to fetch him.”

“You don’t have him? Can you call your boy and tell him to forget James? Please? We can work this out without him. I’ll do whatever you want. Just leave him out of it.”

“Take down my number, dear, and call me if there’s trouble. Traffic or anything. Have you got a pen?”

“Your number’s on my phone.”

“It is?” She hisses at someone.

“What do you want with James?” I ask.

“The fourth dimension,” she mumbles. “We want to test him. You wouldn’t understand and you need to catch your flight.”

This could be Frameshift Corp. I criticize genetically modified organisms in every lecture at Oregon Health and Science University. GMO’s are the grim reaper of genetic diversity, one of the things between us and extinction. “Ma’am, I can’t let this happen. This kind of emotional trauma could send James back into depression. He’s starting to sound normal, finally.”

“Normal. That’s interesting,” the woman says.

“I’m pretty sure you’re with Frameshift, so you’re talking genetics, not string theory. Your fourth dimension is time. You’ve probably got base-pairs lined up for a mile, looking fine on paper. But something’s killing the host. I’ll bet it’s a timing issue.”

I pause and she groans, but doesn’t speak.

“I’m right, then. Listen, whoever you are, you need me. I’ve got seventeen layering techniques that double as time-sequencers. If one of them doesn’t fix the problem, I’ll find something else that does. You can take my words to the bank.”

“My goodness,” she says. “I don’t often get goose-bumps. Perhaps we should test you.”

“Don’t insult me. You’re familiar with my work. All you need to do is forget James, and I’ll come work for you. Legitimately. I’ll sign a stinking contract. Nobody has to be kidnapped.”

A shooting star streaks away from the earth and barely registers as going the wrong way.

“But Ma’am, I’m telling you, if you scare James or bother him in any way, I’ll make sure Frameshift destroys you. Think about it. Once I’m inside, it won’t be two days before your CEO knows he needs me more than you.”

“You insist I’m with Frameshift, but…”

“Screw this, Ma’am. Tell your thugs to look for my body in the ocean beside the South Jetty in Astoria.”

“What are you saying?”

“I’m going to drown myself. I’ll be dead in twenty-five minutes. You won’t need James when I’m gone.”

I hang up with a racing pulse.

Maybe I should have mentioned that my second condition, M5, is acute monocytic leukemia. Diagnosed three days ago at Kaiser. I haven’t told anyone yet. I’m supposed to start chemo tomorrow, but M5 doesn’t respond well. It takes you out in a month, sometimes. I’m just thankful I found the new shrink for James.

James is going to be OK. That’s all that matters now.

Chapter 2

Brittle Beliefs

I’m breaking the speed limit in the Prius, heading for the South Jetty to drown myself, but I need to say goodbye to someone first.

I push James icon on my phone and pull up in front of a vacant lot beside the house I used to rent in Astoria. The Prius engine dies automatically. James’ phone is ringing.

A skanky black cat trots up and jumps on my hood. His nails click as he lands. He walks silently toward me leaving smudgy footprints.

Jame’s voice comes through the car speakers, “Yeah.”

I set my phone in a cup holder. “Someone’s trying to kidnap you. Grab your keys and get out of the house. Run to the car. Drive to the police station fast as you can. ”

“For reals?”

“Yeah, I’m not kidding! Go. Hurry! I’ll stay on the line.”

“Got to find my keys,” he says.

I open the glove box. Two cans of cat food are left. I’ll open both.

“On the floor by the foot of your bed.”

“Won’t be there.”

“Just go look. Hurry!”

I open my window, put my arm out in the usual way and the proud little thing marches up my arm, rubs his matted fur against my face as he climbs down to my lap and curls up.

“Herpes, you little tramp.” I sneeze. When he first came to my patio door demanding attention I had no idea I was allergic. First it was just itchy eyes.

I open both cans of cat food with an old round-bladed device I remember from childhood when it was shiny and had a place in my mother’s kitchen. I dump the catfood into a plastic bowl that’s usually sliding around on the seat beside me. Smells like fish. Herpes springs to his feet and begins that delicate gobbling technique. His ribs are showing again. Poor little thing, out here starving. “I’m sorry I can’t feed you again,” I tell him. “I won’t be coming around anymore.”

I try to pet him but he doesn’t allows distractions while he’s eating.

He has a worn leather collar with a dangling ring that must have held a happy tag with his real name on it. Once. I wonder who he was.

He finishes the whole pile of food before I’m ready to say goodbye, then steps back into my lap to let me pet him. Three times is all. Then he jumps out, lands confidently on the road and looks up at me.

“Goodbye, sweetheart,” I tell him. “I wish I could…”

A van rumbles by and scares him away.

I put the two empty cans in a plastic grocery bag, twist it tight, tie a knot and set it on the seat beside the bowl. Someone else will have to take it to the trash.

“Good call,” James says. “They were right by the end of my bed. It’s spooky how you do that.”

“It’s just luck,” I tell him. But lately I wonder. This time it was an image of his keys. Sometimes there’s no image, just a wordless thought. “Get in your car. Hurry!”

I hear his feet on the old wooden floor at Grandfather’s house. Actually we called him, “Ojiichan,” not Grandfather, but it means the same. The door of the old Ford slams. Low pitch. The starter churns.

The sun isn’t up yet. Jetty Road looks empty as I make a right turn onto it.

“Yo,” James says. “You there?”

“Yeah. Drive straight to the cop station. You know the way?”

“Take a wild guess,” he says.

He was arrested for underage drinking in front of Starbucks not long ago. In broad daylight.

“I’m not saying you’re a moron, James, but now that you mention it…. God, I love you.”

“Ditto, but no need to get all… Whatever. Hey, I never-one knew they kidnap teenagers. You sure about all this?”

“Yeah.” I wake up a few neurons with a neurofeedback technique I learned in a research lab at Yale. They kept asking me if I’d ever been hit in the head. No. I can make an EEG trace jump at will. I learned it with electrodes pasted on my head, staring at squiggly lines on a monitor. Trial and error, bottom-up science not the mythical top-down BS they preach.

Neurofeedback wakes you up like coffee, but some people have memory loss. I should be so lucky.

“Keep an eye on the road behind you,” I tell him. “Somebody could be following.”

My peripheral vision is strange now. The trees… swishing past on both sides of the road. They grab my attention as if they were in the center of my field of vision.

“Nothing’s behind me,” James says.

I ease off the Prius’ gas pedal, pass a crow on the dotted line and watch it hop away in the rearview mirror, wings our angelic. Tough immune systems, those little guys, eating roadkill and living to tell the story.

“The kidnappers are Frameshift goons,” I say to James. “That’s my theory. They’re trying to recruit me.”

“Like into the Army?”

“Same idea.” Should I tell him? Not while he’s driving. “You shouldn’t drive and talk on a cellphone, you know. Under normal conditions, I mean.”

“Pot calling da kine black.”

“No, I got a hands-free setup. Matter of fact, I’m driving right now. To the South Jetty.”

“Some of us drive Ojiichan’s old Ford, you know.”

A motorcycle’s coming at me in the other lane. One loud headlight. It passes with the infrasound of an old Harley. The wide back tire, long chrome pipes slanting up. I wanted to ride one of the old beasts before I died. My legs wouldn’t be long enough though. I bet.

“What’s the South Jetty?” James asks.

I shouldn’t have brought it up. “It’s a rock wall that goes out between the ocean and the place where the Columbia River dumps in. South side. When are you moving in with the Hadano’s? That was supposed to happen three months ago.”

“I don’t know, pretty soon,” he says. “But you don’t have to worry about it. I told the social worker I’m living there now. Mrs. Hadano backed me up.” James shifts into Mrs. Hadano’s voice: “Yes, James is moved in already. Part of da family.”

“The Hadano’s are rare people,” I tell him. “Don’t make them lie for you.” I hate to nag. “How close are you getting to the police station?”

“I’m looking for a place to park,” he says. “Holy Smokes. There’s this Haole dude in a rental car. Following me, I think. I’ll find out.”

“What type of car?”

“Yeah, he’s tailing for reals. I turned up an alley and he’s coming behind me. Driving that thing you drive. The Prepuce.”

Prius, James. “Lucky thing. OK, when you get out of the alley, turn right, go 20 feet, stop and put it in reverse. You’re going to ram him the instant you see him. Go for his right front tire. Mess it up so it can’t move when he turns the wheel. Then drive away as soon as you can.”

“That’ll ruin my car.”

“No it won’t. The Ford’s a tank compared to a Prius.”

“You better be right.” He takes a deep breath. “I got it in reverse. Here’s the dude’s bumper.”

“Floor it!”

There’s a crunch and the sound of glass.

“No prob,” James says. “I’m driving away.”

“Good man.”

“The dude’s running after me on foot.” James laughs.

“When you get to the cop station, don’t park, just drive up close to the front door, jump out, leave the car and run inside. Fast as you can.”

“Do they let you park out front? I don’t need another ticket.”

“Use your head, James! Kidnappers are killers. Do exactly what I tell you, for God’s sake!”

“I was just asking.”

He gets quiet. Any expression of anger was off-limits in our family. It didn’t matter if you were saving someone’s life or destroying the ozone, anger meant you were wrong. You got silent treatment.

“Where are you?” I ask. “Talk to me.”

“Side of the road, basically. In front of the cop building. I’m leaving the car, like you said.”

The car door slams with memories of Ojiichan, the first Buddhist Priest on Oahu. I took his alter back to Okinawa after he died. That was the first I’d heard of his fame in Japan. The Buddhists called him, “One of The Five.” I don’t speak Japanese and my translator didn’t speak much English, so I couldn’t figure out who “The Five” were. But it’s an interesting coincidence that our ancestor, the great Samurai, Musashi, wrote The Book of Five Rings.

“I’m inside,” James says. “There’s this lady here, but she don’t look like a cop.”

“Hand her the phone, I need to talk to her.”

I hear a woman saying she’s busy. She tells him to take a seat. Here it is. That feeling. I’m telling you, I want to reach through this phone and strangle her. What’s wrong with me?

“She’s too busy,” James says.

“Tell her somebody’s trying to kidnap you.”

He does, and she gets on the line. “This young man tells me he’s the victim of a kidnapping attempt and you’re his older sister. Is this information correct?”

“Yes.” I give her my name and the highlights, trying not to sound like the teenager I still am. She agrees to keep him in a safe place until a police officer can talk to him. That’s all she can guarantee.

A squirrel darts out into the road ahead of me and I swerve to miss it. I shouldn’t be doing seventy on this narrow road.

The phone reception gets sketchy as I drive into a dirt parking lot near the South Jetty. Logs outline the perimeter. A dirt slope leads down to the river beach ahead of me. I could drive down there and get stuck, but I’ll park. Save somebody the headache of pulling my car up the slope when they figure out it was the dead girl’s ride.

James gets back on the phone. “Hey.”

“Listen, I’ve got leukemia.”

“You mean…”

“Cancer of the blood,” I tell him. “Odds are, it’s going to kill me in a month or two. But you need to understand, the kidnappers are after me, not so much you. They only want you so they can force me to work for them. But I’m not doing it. I haven’t got long to live anyway, so…”

“What the hell are you saying?”

“If I kill myself, I won’t have to work for those people. I can’t stand what they’re doing to the world. I won’t be part of it.”

“This can’t be happening.”

“Listen, James. None of this is about you. If we’re lucky, they’ll leave you alone once I’m gone. You won’t be valuable to them when I’m in heaven.”

“You can’t kill yourself. You can’t do that.”

“I’m dying one way or the other.”

“They must have drugs. People get rid of cancer all the time.”

“Not M5b. The stats are dismal. The chemo makes you sick as a zombie. Your hair falls out. I’m not doing it.”

“But you got to try.”

“No. You need to try. Try not to get depressed when I’m gone. Try to find something to believe in so you’ll be a decent influence on the world when you’re famous. All this stuff about no God, no good, no evil. Forget it. It’s bull. You’ve got to believe in something. Something that’s not so brittle it breaks when the aliens land.”

“What?” He gasps.

“Atheism and fundamentalism are brittle. They’re both going to break… when the facts come down.”

“I can’t believe this.” He’s on the edge of tears. I know the sound.

“You’ve got heavy responsibility on your shoulders. Listen to me. Nobody has more influence than a rock star. Nobody in this world. You were born to be famous. You’re like John Lennon. You’re a genius with melody, James. Literally a genius.” I’ve never been able to convince him of that. “You’ve always made me so proud. Everything you write. And you got the singing voice to match.”

“You can’t…”

“I’ll be listening to your stuff. And watching you – from the moon, I think.”

“The moon?” He’s crying now. Normally he cries over great songs and sad movies, not real disasters. Disasters make him stronger than most people. Usually.

“Who’s going to be the only friend I ever had, Johanna? Who’s going to make sure I don’t party all the time? Who’s going to bail me out… of jail next time?” My phone goes dead.

I try to call him, but a battery icon flashes for a second then disappears. The phone was plugged in all night. I look at it in my mind and see 100% at the top, above the old woman’s number.

This close to the Jetty, I’m starting to feel a little hesitant about suicide. James and I didn’t even get to say goodbye. It’s cruel.

I remember Ojiichan saying that our existence isn’t real. Get rid of all attachments and nothing can hurt you.

I hear a Sabbath School teacher reading from a little pink Bible, “All things work together for good to them that love the Lord.”

But I never was able to become a true fundamentalist. Not quite. I came close for a while but… whatever. I’ve always felt a little jealous of those people. It’s like the UFO club. I want to believe but those things just don’t show up for me.

I’ve got the jitters. I’m going to breathe water, that’s all. It’s the least embarrassing way to do this, and to be honest, I’m more afraid of embarrassment than drowning. It’s a Japanese thing, I think. Completely genetic.

I get out of the Prius, face the cold salt wind and walk toward the tall, curving breakwater. Its beauty is gone today. I put it side by side with a mental image from the last time I was here. The sun was up, but otherwise the images match.

I was standing right… here.

I wonder if beauty is still there when you can’t see it.

Chapter 3

Buoyancy

I’m standing on the spine of the South Jetty as the tide goes out. I’m far enough from the shore that I won’t be able to swim in if I have second thoughts about suicide.

To the west the ocean horizon is cloudless but vague in the pre-dawn twilight. To the south the beach stretches on forever and the inland hills merge with a blue-gray hydrocarbon haze. The waves below are immature things that belch up abruptly from the black depths and spit white foam across the dark volcanic boulders that form the steep sides of the jetty.

I keep starting to write in my buoyancy journal. In my head, of course. Everything’s there. Every word I’ve ever read or written, the reams of base-pair sequences from work, and every detail of every day I’ve breathed air since I was 23 months old.

When things get me down I make a list of the reasons why they shouldn’t.

First off, I shouldn’t feel bad about what I’m doing here because I’m defending James. That’s honorable. Second, I won’t be lying in a hospital bed with tubes in my veins and everyone feeling guilty for not dropping everything and sitting bored stiff with me until I die.

My buoyancy lists are never long, but they’re powerful against depression. I read them slowly, one word at a time, over and over until my subconscious mind, the big math wizard who hardly speaks English, understands. And I feel better. It’s like magic. I want you to try it.

I’m going to leave my boots on, I guess. But I really love these things. They’re size five, extra wide. Hard to find. I better take them off so someone else can use them.

I almost forgot, Ojiichan’s chopsticks are still in my hair. They’re antiques, engraved with the Japanese character for poison – I don’t know why. I pull them out of my hair, take off my boots and then lay the chopsticks sideways across the toes. I hope no one steps on them.

It’s fifteen feet down to the busy water – surging and receding. I’m not afraid of heights, but I’ve always been chicken about jumping off high-dives. It’s the falling. I hate that feeling. Plus I’m a terrible swimmer. My body is too dense. I’m not all that skinny, so it really doesn’t make sense.

OK, just go. Jump in.

My knees are bent. This is it.

I’m holding my breath… Not sure why I’d be doing that. It’s kind of the opposite of why I’m here.

Now I’m over-thinking.

A truck’s coming on Jetty Road. I should do this before it gets here.

Come on, Johanna. Now!

It’s not a truck, it’s a Hummer. No, it can’t be Maxwell.

I told James about him last week. A guy I met at work. A child psychologist who deals exclusively with depressed kids. Once or twice a month Maxwell shows up at work as early as I do and corners me for small talk.

I suck at small talk.

“How ’bout those Seahawks!”

Forget it.

How ’bout Max Planck? Energy only comes in small digital packets: Planck’s constant. If that’s not weird to you – if that doesn’t turn your world upside-down, I’m afraid we’re different.

Earth: Eggheads and Jocks.

Maxwell’s both. So is James in his own way. I’m just an egghead. Though I do push weights and use the treadmill. And I can lift a tall stack of books, let me tell you.

Talmage thinks I do too much telling and not enough showing. Don’t worry, it doesn’t hurt my feelings.

The sky is neuromancer-gray now, light enough to show the color of the Hummer which is Army Green. That means it is him. It’s fricking Maxwell Mason. Doing a hundred miles an hour on that tiny road. His life’s probably in more danger than mine at the moment.

Slow down, Max!

It’s a pretty straight road. No traffic at all since that Harley. Max should be fine.

No, I don’t believe that either.

He’s slowing down a little. This is good. Now he’s skidding through the parking lot. This is bad. Dust everywhere. His front tires bunny hop a log and finally he stops.

Man, this is going to be embarrassing if I don’t even have the nerve to jump. People are going to say I was trying to get attention. I hate it when people say that about girls who try to kill themselves and fail.

Nobody’s going to say that about me.

I jump.

I take a breath on the way down and feel like a hypocrite for doing it.

For a split second it’s good to hit the water because it stops that lost-viscera feeling of falling. But under the water the world is black and colder than anything I’ve ever felt.

My arms and legs are kicking on their own. I try to stop but they won’t stop. I try to make myself breathe water but my head is pounding with the cold. It’s like a cluster headache or a good poke in the skull with a screwdriver. I can’t think of much else.

My head breaks the surface. The jetty rocks are three feet away and covered with white barnacles and brown mussels that look like dead incisors. I move away from them, not wanting to be a shredded mess at my funeral.

My arms are weakening from the cold. I finally make them stop paddling, and then force my legs to stop flailing.

I sink.

I blow all my air out and prepare to inhale. The salt water will flow into my lungs. Osmosis will do terrible damage to my red cells. My coughing and gag reflexes will be overwhelmed.

I want to breathe. The desire is growing with every heartbeat. It’s just that I don’t want to breathe water.

Yes, breathe water.

Something grabs my arm and pulls. I’m on my back looking up at the sky with an arm across my chest. It’s a thick arm with Maxwell’s watch on the wrist. I gasp for air and it fills my lungs with the greatest joy I’ve ever known.

There’s a surface beneath us. It rises and lifts us out of the water. I’m on hands and knees looking over the edge of a round, silent thing that’s exactly the color of the sky and the texture of the stingray I touched at Maui Ocean Center on my ninth birthday. A circular opening appears beside me and a female voice with the vaguest Indian accent says, “Come inside quickly, both of you. I’ve never been so worried in my life.” A human hand reaches out and touches the skin on my left forearm and rubs it briskly. “You must be freezing. Let’s get you warmed up.” I lean over the edge of the opening and look down to see her face. I’m startled. It’s Mahani Teave, the renowned concert pianist of Easter Island.

My first thought, stupid as this sounds, is to ask for her autograph. I own all Mahani’s CD’s. She’s amazing. I’m a pianist myself.

The pictures on her CD’s flash by and I make comparisons. This girl’s freckles are in the wrong places.

“Who are you?” I ask and start coughing so loud and hard I can’t hear her answer.

…

Chapter 4

River of Consciousness

I’m shivering inside a UFO.

The ceiling slopes down like a Chinese rice hat to the floor. A red band encircles the room where the ceiling meets the deck. The three of us look awkward – Maxwell, me and the girl who could almost be Mahani Teave.

I missed her name when she said it.

I see codes of consciousness when I blink. Ones and zeros.

I know them as doubly-even self-dual linear binary error-correcting block codes.

They were discovered by a theoretical physicist: S. James Gates, Jr., Ph.D.

This is my favorite picture of him: The founding father and pilgrim of string theory’s DNA. History will place him beside Einstein if rational minds prevail.

Biological DNA also has error correction: A higher mind showing cells how to build nanotech machines to fix DNA screwups. Things like replication errors and the mutations we worshiped in undergrad bio.

But the “illusion of consciousness” is the delusion of flatlanders. Conscious awareness is central to digital physics and independently real.

We are not alone.

We’re side by side on a soft Indian rug. The girl’s legs are crossed yoga style now with the tops of her toes flat against the opposite thighs.

“I didn’t hear your name,” I confess to her.

“I am Vedanshi,” she says, beaming. “The Role of the Sacred Knowledge.” Her expression reminds me of Luciano Pavarotti after an aria.

I was twelve when God’s angel died. I will always love him.

Maxwell’s face is blank. He risked everything for me.

“You both saved my life,” I tell them and lean against Maxwell’s wet shoulder. “Thank you.”

Even if leukemia has its way now.

“Cloaking,” Vedanshi whispers, and the red band fades from around us, the walls vanish, and we’re floating on a rug twenty feet above the ocean.

I see my boots on the jetty next to Maxwell’s jacket. I should feel the sea air, but I don’t. The ocean butts the jetty and climbs its rough boulders, but I can’t hear it.

“I need a mirror,” Maxwell mumbles.

“No you don’t. You look marvelous.” I fake an Italian accent, “Shake your hair, darling… such as it is.”

His eyebrows may have moved. I’m not sure.

“Don’t panic,” I tell him. “All your great pianists fly UFO’s.”

Vedanshi grins and the sun breaks. An orange bead on a hilltop.

Maxwell’s vacant eyes find me. He says nothing.

“I heard the phone call,” Vedanshi says. “I know what the old woman is doing.”

“Purchasing my soul?” I suggest.

Vedanshi nods. “Let’s get your things.”

The Jetty is beneath us but I didn’t feel us move. My boots are inches from my feet. I lean forward and reach but my knuckles hit an invisible deck.

“Sorry,” Vedanshi says crinkling her nose. “Try again.”

I reach down and pick up Ojiichan’s chopsticks, grab my boots, then get Maxwell’s jacket and lay it in midair beside his wet legs that stick out past the edge of the carpet and rest on nothing. A little reluctantly, I snag his ugly climbing shoes, bring them in and smell the rubber.

He watches from a trance.

“Snap out of it,” I tell him. “You seem shroomed.”

“It’s a psychotic break,” he mumbles.

“You haven’t turned idiot,” Vedanshi assures him. “There’s a small mirror I can loan you, but I want it back.” She reaches into the side pocket of the purple robe she gave me, pulls out a square purse, opens it and extracts a round mirror the size of a silver dollar. On the back is an engraving of a woman’s face. Lazar quality. She’s wearing a crown and triangular earrings that float beside her earlobes.

Vivid dreamers know how mirror images lag in dreamland. Maxwell is probably a gifted dreamer and wants to test the reality of this place. I can’t blame him. It’s weird.

In the past I’ve tested with mirrors, but I’ve found they’re harder to track down than bathrooms – in dreams, I mean.

Rule of thumb: If there’s a mirror, you’re not dreaming. You’re totally sitting in a classroom naked.

“We should leave,” Vedanshi says. “She’s coming. I don’t want her to discover me.”

With the sun up, Vedanshi’s white blouse is orange and short. It leaves an inch of skin above tiny-waisted harem pants. She either works out or never eats… or has issues with her thyroid.

“You two may want to close your eyes,” she says as the Jetty drops and the mouth of the Columbia River shrinks into a falling coastline.

The horizon rounds down and the Earth becomes smooth and blue to white on the sun’s side.

There was no lurch of engines, no whiplash, not even a hiss of wind.

I glance at the sun and get dots following my eyes. Canada is endless. The overhead is black and radiant with stars. The swath of glowing velvet is an edge-on look across a spiral galaxy.

This is the “near space” I’ve read about, but it feels nearer to Heaven. I’m overcome with affection for our magnificent little round home. She’s cute, miraculously great but humble. Wise and still innocent.

This is warmth I’d never imagined.

I grip it the way James’ therapist says – holding bliss in a 30-second headlock to myelinate the neurons of joy.

Listen now. Happiness is a skill, like training your fingers to do three-against-four on Chopin’s Fantasy Impromptu in C# minor. Or figuring out how to sing with vibrato as a child, then spending the rest of your life trying to forget.

Craning at the most numerous Seven Sisters in captivity, I lose my balance and grab the front of the carpet to avoid Revelation’s fall from Heaven to Earth.

“My ship believes she’s twelve thousand years old,” Vedanshi says. “Her name is The Ganga.” Vedanshi looks at the rug and seems to talk to it. “Anyone can speculate about axial precession.”

Maxwell touches the mirror’s edges only, holding them with thumb and finger. He seems dissociative the way he’s checked out.

“So you’re from Earth?” I ask Vedanshi.

“Of course.”

“Well, you never know. You crashed the party in a UFO.”

“Yes,” she says, but shakes her head, no. “I’ve seen UFO’s on your internet but I don’t know if they’re real. We didn’t have them in my day, and I was never old enough for the talk.” She taps her knees to put quotation marks around, “the talk.”

“What’s ‘the talk’?”

Her brow furrows at Maxwell spinning her mirror, but she lets it go. “In my day, when you turned 18 you got ‘the talk’ from your parents. It was about free will – or so they said. But I could tell there was more. When I was in pyramid triage for the river – a test to identify pilots – I made friends with a girl whose big sister got ‘the talk’ and then started whispering to shooting stars. She wasn’t loopy before that, supposedly.”

Below us to the south, bright sheets of white flash over Mexico and red sprites blink over the clouds.

“What would make anyone whisper to a meteor?” I ask.

“Aliens?” Vedanshi shrugs. “We heard strange voices in the river before the asteroids hit. I still wonder if they were real – you know – literal words that The Ganga somehow couldn’t interpret. It’s doubtful. Her linguistics are advanced. But why would anyone subvocalize nonsense in the river?”

Glossolalia, I don’t know. I look at Maxwell. “This is no ordinary UFO!”

No response.

Vedanshi nods solemnly. “The Ganga taught me English – which didn’t exist for us four months ago.”

Maxwell is mouth breathing. That’s the last straw. I lean over and kiss the side of his face. It’s salty. “Buck up, soldier. You’re making me worry.”

“Sorry,” he says and shakes the cobwebs.

That was the first time I’ve kissed a guy. True, I was raped once, but no kissing. I was eleven.

“You’re from Earth,” I remind Vedanshi. “So where did you get this thinking machine?”

“They did it on purpose,” she says, then draws an expansive breath. “I should back up. The very oldest ships had accidents. Their non-locality buffers got out of sync with the gravity lifts sometimes. So for an instant you had movement during the nonlocal swap.”

I nod.

Maxwell leans back on his hands. “You lost me.”

“Anything using quantum non-locality has to be nailed down,” she says. “So it’s motionless to the buffers. But the primitive ships shifted structurally – at nearly the speed of light if it happened with the horizons burning.” She searches Maxwell’s face. “Nonlocal point swapping horizons?”

He squints. “I have no idea what you’re talking about.”

“High subluminal velocities turn nanoseconds into thousands of years,” she explains.

“It’s special relativity’s version of stasis,” I tell him. “Slows your clock.”

Maxwell smirks.

“You’re never heard from again,” Vedanshi says. “Unless you’re lucky enough to wind up in this post-cataclysmic dystopia.” She looks down at the Earth with a half-smile. “The old woman came from the first part of my era, I think. I finally saw her vehicle. It’s phallic, which is retro. And it has to be early because every thought gets out.”

“Every thought? What do you mean?” I ask.

“The river?” Vedanshi asks me back.

Maxwell and I shake our heads. I hate to admit when I’m lost.

“The fundamental unit of reality is consciousness,” she says, “not matter, energy or space. They’re derivative. Pilots use the river of consciousness to communicate with ships and other pilots. I don’t know why we call it a river, it’s more like a sea, or the pixels of an infinite hologram.”

“Now that I can understand,” I tell her.

“In the earliest vessels privacy filters didn’t exist. The old woman’s ship must be dangerously ancient because I hear every word she thinks. I’ve even seen a few cortical images from her occipital lobes.”

I feel my heart racing. This is the mother lode everyone dreams of. I wish I had longer to live.

“A few months ago,” Vedanshi says, “I heard the woman thinking about a young geneticist who manipulates terabytes of base-pair language in her head with no implants. Totally impossible. My mother’s best women with cortical enhancements couldn’t hold a ten-thousandth of that in working memory, let alone juggle it. So I had to meet you, Johanna. Because, as you say, you never know.” She puts her hands together yoga style and bows her head like Ojiichan did in his Temple. “This morning I heard the woman threatening to kidnap your brother. Then you went off to drown yourself. I sort of panicked trying to find you.”

“So… you can hear phone calls?” Maxwell asks.

“The woman was inside her ship,” Vedanshi says.

“Yeah, she was in her ship, Max. Keep up.” I scowl warmly.

He gives me a hint of a grin.

“You have to master the river of consciousness before you pilot,” Vedanshi says. “Pilots are born with an extra gyrus on their parietal lobes, but the phenotype is no guarantee you’ll make it.”

Einstein had a parietal lobe anomaly. Suddenly I want an MRI.

“You said 2015 is a post-cataclysmic dystopia,” Maxwell says.

Vedanshi nods. “We’re probably six to twelve thousand years into it. There are four in recorded history.” She pats the rug beside her.

“The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse,” I hear myself saying, and the verses open in my mind.

“Your unique feature is the loss of ancient records,” Vedanshi says. “From what I’ve read, your scholars get things backwards. The Grand Canyon took millions of years and the pyramids took twenty. I don’t see how anyone with eyes could believe that.”

“What ended your era, a comet? A flood?”

“A series of asteroids,” Vedanshi says. “The small stragglers landed near Madagascar and left beautiful deposits.”

The Earth rotates beneath us. Africa comes around with Madagascar to the east.

“This is the best one,” she says, pointing down. “See the feathers? It’s like a bird’s wing.”

I’ve seen these before. To me it’s like someone dumped soapy water in the dirt. This one’s several miles long.

“Geologists say these were made by the wind,” I tell her.

“Not true.”

“What, then?”

“This is a piece of the Earth that broke free when one of the smaller asteroids hit. I saw it happen. It flew through the air at thousands of miles an hour. It came from the seabed over there.” She points east to a spot in the Indian Ocean where I’ve read there’s a crater. “This piece flew out at a low angle, glowing like lava with a tail of smoke and steam. The trees exploded when it hit. It was fluid, colloidal, and flowed into this nice winglike shape. A small tsunami crept up a bit later but couldn’t wash it away. Unlike the previous day’s waves that razed everything.”

“The asteroids didn’t hit in one day?” I ask.

“No. The big ones came on the first day. A few smaller ones hit that night, and the tiny one that did this artwork touched down at sunrise. It might have been the last one, but…”

“So… Wait now. Are you saying the bigger asteroids made tsunamis that washed away their own impact deposits?”

“Yes, on day one. But I don’t think you’d call them tsunamis. They weren’t like Japan’s waves on the internet.”

“What was different?”

“They were huge. They moved like life forms – boiling over the continents without slowing down. Each one would start as part of an impact explosion and spread out in a circle with the circumference increasing until it matched the circumference of the Earth. Then it moved on around and the circumference shrank, keeping its power about the same until it narrowed down to a point and crashed into itself on the opposite side of the Earth. There was lightning and the loudest thunder. Water and debris shot up miles into the air. The big ones smoothed out everything in their paths, including their own ejection deposits. Later when things settled down and the small asteroids began to land, their water action looked more like Japan’s tsunamis. They were too weak to clear their deposits for the most part.” She looks down at the ground. “But if you really look, you can see shadows where some of them were washed away, too. Over there.” She points inland. “It’s like a stain.”

The Ganga moves closer.

I kind of see what she’s talking about in the distance. But the wing chevron is impressive down here.

“Max, I’ve read that it’s six hundred feet thick at the edges.” I point to the wingtip.

“Looks pretty flat.” He tilts his head to look down my arm, and I point again. His buzz cut brushes my temple. His collar is wet.

“Take off that shirt and put your coat on,” I tell him.

He grunts.

The Ganga moves lower, as if to show us the height of the wingtips. Maxwell whistles when we come down over the lip and really see one of these things edge-on.

He’s twenty-five. When we first met a few months ago he introduced himself as an aging surfer. So he’s probably not cold at all in his wet clothes. The bum.

I jab at him with an elbow.

He ignores it.

A cell phone starts a weak rendition of “Surfer Girl” and Maxwell digs it out of his coat, sees the number, then hands it to me. “It’s James,” he says.

I put it on speaker by habit. “James, are you alright?”

“That guy I rammed was a cop. I don’t know where they’re planning to take me, but he’s filling out a bunch of paperwork and sounds extremely pissed off. He’s got handcuffs. I hate those things.”

“Where are you?”

“He’s taking… He took my phone.” The connection goes dead.

I look at Vedanshi. “A cop in a Prius? I doubt it.”

She takes Maxwell’s phone, places it on the rug in front of her. The Earth drops like a lead ball from a bomb bay. We streak through white haze and across a blur of blue ocean. A glimpse of land flashes by and our impossible speed turns to a dead stop without making us even bob our heads. We’re fifteen feet off the ground in front of a police station in Honolulu.

James stumbles out with his hands cuffed back and the Haole pseudo-cop shoving him. The man kicks James’ legs and knocks him off the curve to the ground.

“Let me out,” I tell Vedanshi. “I’m going to hurt that man.” I feel the cold DNA of my ancestor, Shinmen Musashi-no-Kami Fujiwara no Genshin, the greatest and by far the deadliest samurai who ever walked the Earth.

I was eleven when I strangled a male adolescent chimpanzee with my bare hands. It’s the same feeling now.

Chapter 5

Rage

“If it could be demonstrated that any complex organism existed which could not possibly have been formed by numerous successive slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down. But I can find no such case.” Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species.

The moon’s size and distance were selected so that its silhouette would precisely cover the sun during an eclipse, at least sometimes.

Call it blind luck. But what are the odds?

If the duck billed platypus were known only as a drawing in Egypt…

Could science tolerate more than a “myth” about a mammal who laid eggs, offered milk but no nipples to her hatchlings, hunted under water with eyes and ears closed using electroreception unknown to other mammals, stabbing her victims with poisonous spikes on her hind legs, then grinding her food with rocks in a toothless duck bill only to swallow it into a GI tract with no stomach?

These uncomfortable facts caused the skeptical elite of yesterday to insist that she was a hoax.

Just as we assume the bird-man of ancient Egypt was religious fiction.

But what if we are wrong?

The inconvenient truth about the platypus is that she screams of intelligent design. Not only of the original coding of a supreme mind but also of genetic tampering.

When new research pulls back the curtains on this duckish mosaic with in-tact blocks of DNA spliced from diverse species – who will hold the robes of the outraged thought police as they stone the young heretics, boycott the journal that published their work and fire its editor?

I refuse.

Rage, like denial, is a decision, but only if free will exists. Otherwise the Queen of Hearts was temperate in shouting, “Off with their heads!”

It’s fifteen feet down to the street. Not much traffic. My lips are sticky with brine.

When that man below us kicked my brother to the ground I wanted blood, but now the words that Nietzsche hated come to mind:

“Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.”

The Nazarene.

A certain Buddhist Priest also haunts me:

A

nymph

in pale feet

rides the opera

to a spiral staircase.

Lightning hair, dark voices

strike within her yielding gall.

Silk jinn brass restrains the lip strings

beneath her tears that fall and glare inside

a secret box.

Ojiichan wrote this at a recital where I sang “Un bel di vedremo.” My father translated it from the Japanese. That was three days before the accident on the Pali. Forget that now.

In the legend of Utsuro-bune, a red-headed woman landed in Japan in 1803 inside a “boat” that resembled a rice cooker with windows and strange writing on the walls inside. She spoke no Japanese, clutched a wooden box, and as the story’s living soul, she showed respect to the Japanese fishermen.

This is why her legend survives.

In this opaque neo-infinity, science is forever young and speculative. To forget this would be disrespectful and short-sighted.

“Remote viewing of long-term goals” would be a dissertation worth defending.

But ruling elites say the average human chooses short-term pleasure over long-term riches. Thus we need laws against natural selection. A childproof world.

Complex problems rarely have such simple solutions. Here’s the picture of that principle…

Dr. Seung’s crowd-sourcing of neuroscience recruits us to map the soul. With our help, every microscopic neuronal connection will be recorded in three dimensions, someday re-created and reanimated.

The handshake of science and religion has always been immortality.

And we thought the ancient Egyptians were primitive with their mummies, that silly religious talk and all the “incidental” preservation of royal DNA.

Who looks silly today?

So if natural selection brings genetic wisdom, why hamper it with childproof laws? Do the secular elites know something they’re not telling?

Plenty.

Perhaps a hand full of them have even noticed that logic requires a Prime Source of our genetic commands, a foundation for trust, and access beyond space to allow a fleeting choice of love over hate.

This choice comes to me now…

To spare this guy who’s kicking my brother, or to fight him.

The way I’m feeling, I would crush him easily.

That’s not logical, I’ll admit. Strange things happen to me when I get angry.

I fought Moody and thought I had defeated an enemy. Instead, I murdered James’ closest childhood friend and lost my innocence on a kitchen floor covered in my own blood.

The carpet is damp beneath me. I’m shivering and sweating. It’s a fever.

Vedanshi shifts and sits on her heels again. “If they recognize your face, the old woman will wonder how you got here from Washington. You need a disguise.” She reaches into the deck and pulls out a bra, then a dangling sock which she hands to me. “You should put this over your head, I think.”

I put it on quickly. It smashes my nose but I can see through it.

“If the man has a gun, The Ganga can disable it,” she says. “Theoretically, I mean… We’ve never actually done it.”

Maxwell rises to one knee and encounters the ceiling of a UFO with his head. “I got your six,” he says.

“No,” I tell him. “Better you stay here. You’ll scare the guy.”

“So you’re not going to hurt him?” he asks.

“Not if I don’t have to.”

“Good,” Vedanshi says. “There’s a break in the traffic. Scoot under a car so no one sees the decloaking.”

The Ganga dips to street level. I crawl out of its cloak and roll under the car that’s parallel parked behind the Prius. I reach out to see if my hand disappears into The Ganga. It doesn’t, so I scoot out into the street, stand and move between the pseudo-cop and my brother.

The man steps back and pulls a gun, almost dropping it in the process. “What’s with the mask?” he asks.

There’s a wedding band on his left ring finger and cowboy boots below a sagging uniform that would fit a much taller, thicker man.

“Tell me why she’s cursing the dumb Haole in the cop suit,” I say to him.

His jaw falls open but no words come out.

I glance behind me at my brother. “Did she say to break this boy’s knees?”

“She sent you?” the man asks, his forehead lined.

I nod, fold my arms then shake my head at him. “No one can reason with her when she’s like this. You’re a family man, so I’ll try to get you off the island before she snaps. No reason you should die.” I look at his boots. “What is it, Texas?”

“I’m from…”

“Shut up. Let me think.” It’s an uncomfortable show. I don’t really need time to think.

He purses his lips.

I stare at him for a moment. “Here’s your plan. Fly home, get your family and disappear. That’s your best chance.”

His eyes open white all around. “She’s that mad?”

“I haven’t seen her like this before. I’ll take this kid. You need to vanish.”

“How was I supposed to know he’d go straight to the cops?”

“You’re right. There’s no way anyone could have predicted that. But listen, whining won’t help you.” I reach up and fasten a button on his uniform.

His shoulders slump and he tucks his gun away.

“I’m sorry,” I say. “Maybe there’s something good I can tell her about you. Got anything?”

He stutters.

I tap his chest with my fingers and hold out an open palm. “Cuffs?”

He takes a key from his pocket, gives it to me, then ducks into the driver’s seat of the Prius. “Tell her thank you,” he says. “My son’s showing signs of empathy.” Tears well up in his eyes.

“Empathy’s good. I’ll give her your message word-for-word. Is your boy getting the I.M. injections?”

“No, I.V. Some DNA thing. I never get it right… Menthol Asian?”

“DNA demethylation,” I suggest.

“Yeah, that’s it.” He squints up trying to find my eyes through the sock I’m wearing.

“Look, just tell her she’s welcome to kill me. Tell her I’ll do it myself, in fact… If she’ll just please, please keep treating my son. That’s all I want. I’ll do anything.”

“Don’t think that way. Suicide would make things worse. For the rest of your son’s life.” I can’t believe I wanted to hurt this poor guy. “Give me your phone number.”

He reads a number off the back of his cell phone.

“Go home,” I tell him. “Get packed. Get ready to run, but wait for my call. I will call you. Whether I can cool her down or not.”

“Thank you.” He reaches out, squeezes my wrist, pushes a button on the car’s dashboard, then rolls a few feet away before the gas engine comes to life and takes him out into the morning traffic.

I turn to James. “Cameras are watching. You don’t know me.”

He chuckles. “You look like a bank robber.”

He seems stable on his feet. “Can you walk?” I ask him.

“Sure,” he says. “The guy kicks like a girl.”

“Why does that dumb remark make me want to hug you?” I move behind him and push him along the sidewalk ahead of me. We walk south for about forty seconds, then take a left into an alley and come out behind the buildings into a parking lot big enough for The Ganga. Ojiichan’s Ford sits behind the police station two buildings to the left. I take the cuffs off James and try to say that we’re about to meet an invisible thinking machine, but he’s not listening.

“You were going to drown yourself,” he says. “I got that feeling back. Where you basically don’t want to be alive.”

“I’m sorry, but you don’t have my permission to kill yourself. You’ve got to put Skullcage on the map and carry on the Fujiwara name.”

“Yeah, I know. I really do know. But it’s just that sometimes…” he looks down, “I really don’t care.”

I gently slap his face. “I don’t want to hear the demons right now.”

He’s a little startled but doesn’t say anything.

“Maxwell and a girl named Vedanshi fished me out of the ocean. They don’t know about my leukemia.”

“There’s got to be some kind of treatment for that,” James says.

“There’s not,” I tell him.

His face is so lost. But only for a moment. Suddenly he’s himself again.

“What just happened there?” I ask him. “In you head.”

He looks up and to his left. “I don’t know.”

“Whatever you just did, it’s the secret to a good life. Try to remember it.”

I tug on his left arm and get him to crouch next to me out of camera’s view beside a parked car. We get flat on our stomachs, just to be sure. Vedanshi’s face appears inches off the ground in the parking space beside us. Her head is detached and floating upside-down with her hair on the asphalt.

“Coast is clear,” she says and vanishes, chin first, hair last.

“That’s Vedanshi,” I say.

“OK, that just happened. We both saw it.” James goes into a dense calm and then comes out of it rubbing his eyes. “She’s hot, isn’t she?”

“Yeah. And she’s inside an invisible machine. We’re going to crawl into it now. Parts of your body will disappear on the way in. No big deal, right?”

“Disappear? Nah… really?”

“Don’t freak out on me. Just go. And don’t stand up for the cameras.”

I push him. He moves forward and disappears as if crawling through invisible UFO hulls was routine to him. Complete confidence. That’s James 24/7. Unless he happens to call you late at night from jail. I follow after him and take my place by Vedanshi. James sits on the other side of Maxwell.

“Tight,” James says looking around at the acorn pattern on the Indian rug. He reaches in front of Maxwell and me to shake Vedanshi’s hand. “I’m James. It’s beyond amazing to meet you. You’re absolutely gorgeous, you know.”

“Thank you.” She blushes and shakes his hand. “I’m Vedanshi, The Role of the Sacred Knowledge.”

“The role of… That’s the meaning of Vedanshi?” he asks.

“Yes.”

“That’s got to be the most beautiful thing I’ve ever heard in my life.” James glances at me then thumps Maxwell on the back with an open palm. “Thank you, dude. You look just like your Facebook pictures.” He looks at Vedanshi again. “Thank you both for getting Johanna here to save my ass. I owe you guys… my life, probably. That was one unhappy cop.” James looks at me. “How’d you do that with him?”

“I don’t know, it’s the first time I’ve been that deceitful. I feel like I need to wash my mouth out and take a shower.” I peel the sock off my face, pull it up off my head, then look at Vedanshi. “What do you make of DNA demethylation to treat autism? Could you hear him at all?”

“Every word,” she says. “In the River I’ve noticed the old woman likes to mull over the language of a virus she seems to associate with Autism. It methylates DNA. Epigenetics, you would probably call it.” The Ganga rises ten feet with no tells on Vedanshi’s face. “Would all of you like to stay at my place tonight? It’s not really mine, but… Well, it sort of is now.” She smiles but her eyes are distant.

“Definitely,” James says.

Maxwell nods and I say I’ll do anything that doesn’t involve the old woman. But actually I’m worried about the guy I sent home. And his autistic son. What have I done? I should probably call the old lady and fix this.

“I don’t guess we can do a noodle run in this thing,” James says. “I’m starving.”

“I’ve got veggies in the garden,” Vedanshi says. “Things are growing.” She notices the bra on the rug beside her legs and sneaks it through the deck beyond the edge of the carpet. “James,” she says with a glint, “lean forward as far as you can and look down.”

“Don’t do it,” I tell him.

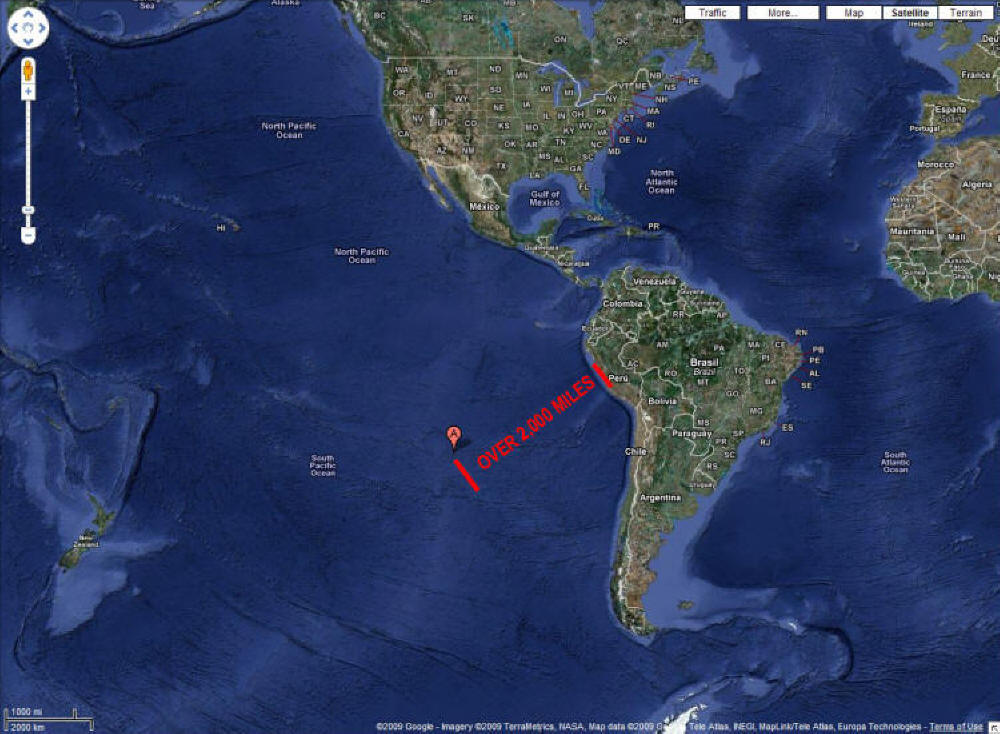

He leans forward and as the parking lot shrinks out of sight and the Hawaiian Islands zip down to dots in the Pacific Ocean, he calmly says, “Jeepers, Mrs. Cleaver.”

I shake my head.

“You were supposed to be startled and impressed,” Vedanshi says.

“I am.” He draws a deep breath and lets it out with a whisper, “God, I hope this isn’t a dream.”

“It’s not,” Maxwell says, as South America rushes toward us and an island off the coast of Chile and Peru comes closer.

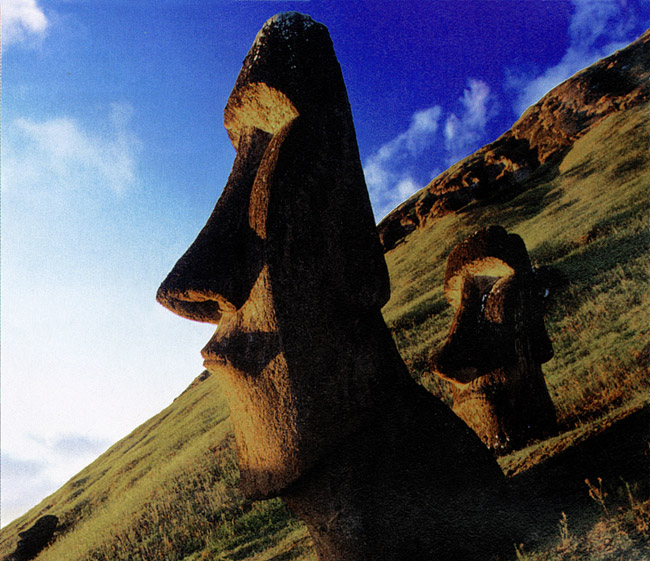

“Rapa Nui,” I say as the island’s triangular shape evolves beneath a flock of small cumulus clouds.

I know Vedanshi is not Mahani Teave, but why is she taking us to Easter Island?

We descend and the ancient Moai give us palpable respect as though they’d been waiting eons to greet us.

The southern end of the island comes close, but we move past it, beyond the two tiny rock islands and into the crystal water. With the hull cloaked we’re gliding forward under the ocean in a saucer-shaped bubble. Visibility is sixty-five feet plus.

“Vedanshi,” James says, “I’m sixteen. How old are you?”

“Sixteen,” she says, “not counting quantum stasis.”

James grins at Maxwell. “If this is a dream, buddy, I’m going to be pissed at you.”

They both laugh as we head straight at a rock wall without slowing.

Chapter 6

Scars

The Ganga stops within inches of the face of a vertical cliff.

Offended fish scatter, small and blue, yellow and rare: the Femininus wrasses.

I can’t tell if Vedanshi is reckless or if non-local buffers and gravity lifts are designed to jar the nerves. At least there’s no whiplash.

Vedanshi closes her eyes. In a silent click we’re hovering inside a large granite chamber with geometric rock walls that have the odd nubbins I’ve seen in pictures of ancient Peruvian ruins.

They remind me of the nubbins on the Pyramid of Menkaure in Egypt. Drain hole artifacts from molds, I would guess.

I wonder if people realize the staggering complexity of designing random block sizes into a high tolerance structure.

Water drips from The Ganga and splashes thirty feet below onto a dark floor. The room is the size of my old high school auditorium on Oahu.

There’s a picture in my head of a small platform somewhere on Easter Island.

The blockwork is similar to the walls that surround us now.

Here’s another platform on Easter Island…

Here’s a close up of an ancient wall in Peru. The trapezoid is about the size of a finger and extends completely through the wall.

“How was this rock work done?” I ask Vedanshi.

She gazes across the room at the opposite wall. “Molten hot granite cement poured into heat-resistant molds of cloned spiderweb. Black widow, probably.”

OK, I was basically right. “Tell me about quantum stasis.”

Her fingers move horizontally across her forehead. “I’ve been in 2015 for four months,” she says. “Alone.” There’s a quiver in her voice. “I’m at the age where pilots start hearing the river. The first day the asteroids were spotted, my mother’s techs gave me a crash course in consciousness – basically how to let a bunch of ones and zeros connect with the machine language.”

“So the brain has a machine language,” I say.

“Sort of,” she says. “It’s a five-dimensional hologram, analogous to the river of consciousness itself. It resembles the physical structure of the universe.”

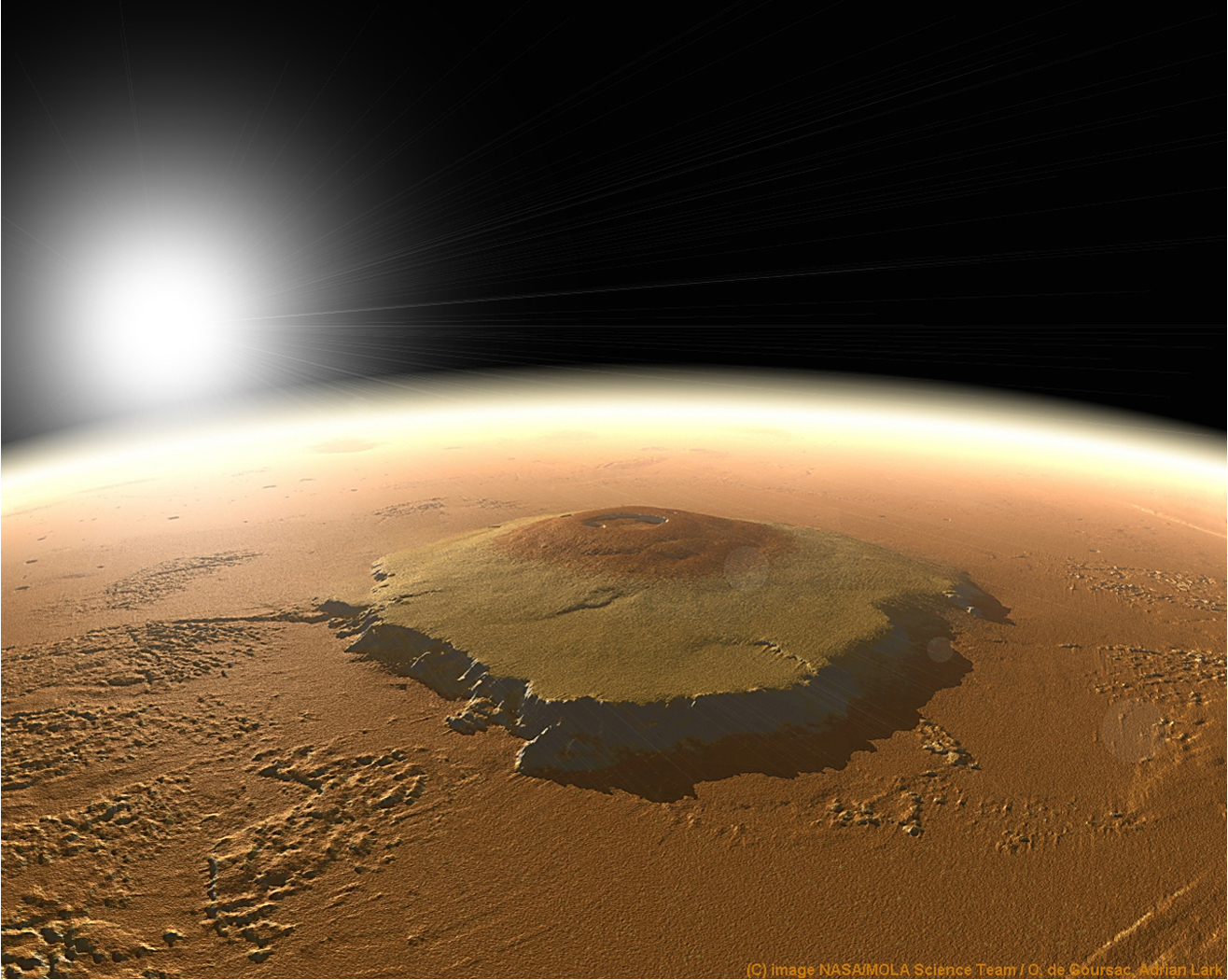

A deep image of my universe comes to mind.

It resembles the cultured hippocampal neurons I sometimes work with in the genetics lab at OHSU…

“Like most things,” Vedanshi says, “our machine language seems to be an analog process at first glance, but ultimately it’s digital. Everything is digital this side of space-time.”

“Which five dimensions are we talking about?” I ask.

“There’s the usual four of galactic space and time,” she says, “and then there’s a fifth that curls outside of ordinary space.”

“That figures. Free will needs some sort of foothold outside causal space.”

Vedanshi nods thoughtfully. “The old woman’s back in her ship, by the way. Trying to find her burner phone.”

“I’ve been seeing ones and zeros all morning when I blink,” I tell Vedanshi.

“Really?” her face brightens. “You could be a pilot in the rough! Try this… close your eyes and slow your breathing.”

I close my eyes but can’t stop breathing fast. It’s the fever. I’m still shaky. Too hot or freezing cold in this robe.