Love is where writing began for me.

I couldn’t hack it when I started writing fiction. I would drudge up a few tedious pages, look them over and feel hollow and exhausted.

I wondered how anyone could muster up enough self-discipline to write fiction.

Yet earlier in college where everyone swam in hard work – and even before college where I seemed to be the only one studying all the stinking time – I deeply enjoyed the few fiction writing opportunities that came.

What had changed after college? I still felt deep down that I was a born writer.

Then one day in my first year of med school, with no plan or purpose, I found myself creating two people who were SCUBA diving off the backside of Molokai, Hawaii. They were ocean-going archaeologists. The viewpoint character was a young man, the other person was a Japanese girl, Johanna, who reminded me of my wife.

I saw Johanna for the first time in 39 feet of water uncovering part of a petrified skeleton, using only her hands. She must have been excited. The viewpoint guy did a double-take because her hands were moving as fast as a machine.

As a writer, something weird and amazing began happening for the first time: a character of mine was showing signs of life.

Intuitively, I knew a lot about Johanna at first glance because somehow she was just like my wife.

So I was literally in love with Johanna before we met.

As she and the viewpoint guy with her (Max) approached the dive boat, she swam up next to him and told him to cover his head.

Then, before he knew it, he was flying through the air and landing on deck.

Johanna, who was suddenly with him in the boat, began stammering through apologies, explaining that a shark had come too close and she’d overreacted and shoved him up into the boat with too much force.

“But how?” Max (and I) wondered.

Maxwell couldn’t stop questioning her and asking about her impossibly fast hands.

Finally she told him an ancient family secret of the Fujiwara clan: there was a recessive trait that had remained dormant for centuries and had never been expressed in a female. Johanna had inherited it with this unprecedented phenotypic penetrance.

It was easy to tell that, in her way of thinking, it was shameful and embarrassing for a girl to be as strong and quick as she was. To her it was boyish and therefore a repulsive quality in a girl. She swore Max to secrecy.

And I fell in love. (With my wife, OK? She and Johanna were the same person at heart.)

From that day to this, writing fiction has been fun and meaningful. At times it feels almost like an addiction. It never seems like work – but I’m not a professional writer yet, so how could it?

One thing: it’s not just an addiction. Writing fiction feels like a higher purpose – sort of a “calling.”

And when new ideas come, creating a place for them in the latest rewrite of Johanna’s story is a powerful force of joy.

Decades after meeting her, I’m still writing about Johanna. The stories change. She’s grown younger as I’ve grown older. She still rivets me to this keyboard.

If I ever get paid for writing about her, it won’t seem right. I’ve always had to work at an isolating and difficult job for money (update: I was a pathologist, but recently quit). It will seem weird if I ever get paid for writing about Johanna.

Not that I think money is a negative thing. I don’t at all.

“May the Lord smite me with it. And may I never recover!” (-Fiddler on the Roof)

But since meeting Johanna, the writing process itself is the only payoff I really need. I’m pretty sure that I need to write fiction in order to be happy.

The hope of finding readers comes and goes. It’s not essential that I find them, but the process of trying can be great fun! All the blogging and exchanging comments with brilliant, fascinating people – it’s a blast! I wish we were all face-to-face friends.

Someday, huh?

But the practical point I want to make about Johanna is the milieu in which I met her: an unstructured environment where the main character was free to act intelligently, free to become, free to decide, and free to experience the natural consequences of her own choices.

The best-selling stories that I admire most are written at the other extreme – around organized plots with detailed planning and outlines.

For me, plotting is the hardest part of fiction writing, and the most neglected. I’m told that it’s neglected even in University creative writing classes, probably because it requires huge mental effort and has a cause-and-effect association with capitalism: book sales.

I think most any average reader (like me) recognizes the value of plot.

I want readers, so I work at my plots.

Outlines seem to help, although Johanna won’t stick to any of mine for long.

Yes, I know that’s nuts. Talk to her about it. 😉

I’m working to nudge Johanna’s life in the direction of a designed, semi-predetermined plot, so she winds up in a “meaningful page-turner” with an active storyline, a few round characters and a dimension that might cause a reader to take a new look at some of our culture’s lamest assumptions.

As a writer, I welcome a compelling plot as long as it bends and steps aside for characterization and new ideas that arrive.

But the reality is – and this is the point of telling you all this – I never would have become a fiction writer if I hadn’t met Johanna in a place that was free of plot and determinism.

My life would never have been enriched by my kind-hearted, strong-willed, genius girl, Johanna, if I’d started as a puppeteer rather than a humble creator with respect and growing love for a “real” person with free will.

Love is where writing began for me.

…

M. Talmage Moorehead

Please opt into my mailing list so I can let you know when my books are ready: Click Here 🙂

…

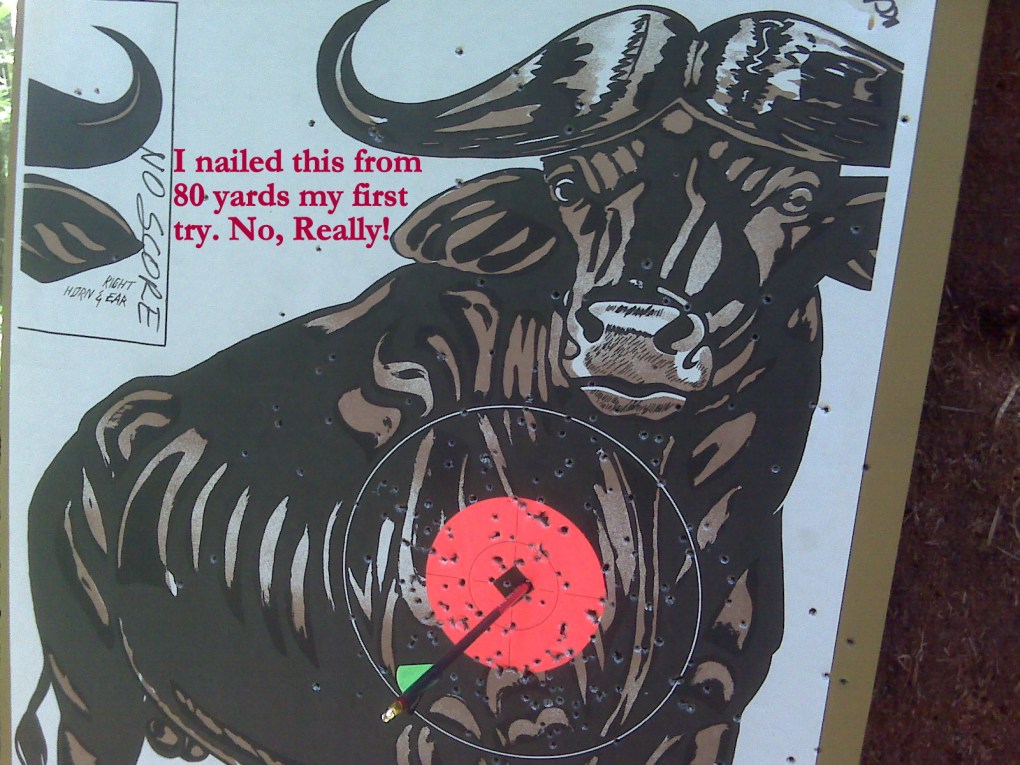

By the way, regarding the picture up top with the arrow inside the squarish bull’s-eye…

With God as my witness, I hit that shot on my first try from 80 yards with my new bow. I’m a novice with bows and arrows. I don’t have a fancy scope like the pros use. I wouldn’t know how to use it if I did. The basic scope that I had wasn’t sighted in at 80 yards. I’m quite sure that I could never hit that shot again in a hundred years – speaking from logic and objectivity, not pessimism.

But the first time I tried it, I nailed it from eighty yards.

What does this mean, if anything?

I keep wondering if there was more than coincidence at work. “But what?” someone might ask. “There’s nothing besides coincidence to explain it.”

Nevertheless, eighty yards is one heck of a long shot for a novice with a new bow without a target-shooting type scope. At the archery range where this happened, only two 80-yard shots are available.

A person only shoots his or her first 80-yard shot at a given target once in a lifetime.

Incidentally, I would not recommend using such an unlikely plot point in a story. It might not be normal enough for fiction. But in real life, stranger-than-fiction things happen…

For instance, Einstein’s time dilation is real and measurable. And the notion that most of the stuff of the Universe is either “dark matter” or “dark energy” is real to the right batch of scientists.

Anyway, this bull’s-eye shot seems as likely as a brand-new writer meeting someone as amazing as Johanna Fujiwara.

When these sorts of things happen, do you think maybe God is trying to tell someone something? Sorry, I didn’t mean to get religious on you. I’m not a fundamentalist Christian anymore, but I’ll always respect those who are.